Matt Kinney’s Mansion Makeover

Jennifer Farley | February 24, 2017 Artist and construction worker Matt Kinney moved to Beacon from Brooklyn in 2003, living in a variety of modest situations—including camping on a friend’s farm—prior to buying a stately two-story 1850 home on Commercial Street last November for an undisclosed sum. The four-bedroom, two-bath, 2,380-square-foot brick house needs lots of interior work and a complete systems upgrade. But the half-acre grounds are heavily planted with mature botanical specimens— bleeding hearts, lilacs, and a variety of trees—so it looks lusciously ordered from the outside, however dishabille within.

Artist and construction worker Matt Kinney moved to Beacon from Brooklyn in 2003, living in a variety of modest situations—including camping on a friend’s farm—prior to buying a stately two-story 1850 home on Commercial Street last November for an undisclosed sum. The four-bedroom, two-bath, 2,380-square-foot brick house needs lots of interior work and a complete systems upgrade. But the half-acre grounds are heavily planted with mature botanical specimens— bleeding hearts, lilacs, and a variety of trees—so it looks lusciously ordered from the outside, however dishabille within.

Just a block off Main Street, the handsome Italianate structure was home to one of Beacon’s three mayors during the 1920s—it’s not certain which one—and if anyone knows particulars about the local landmark’s history, Kinney would appreciate an e-mail. He hasn’t had time to research the historic title records, which are kept in Poughkeepsie, since he works four days a week for master carpenter Patrick Freeman of Freeman Woodworks. Kinney also makes art. With refreshing optimism, he regards his home as a prudent long-term investment, because he can do so many of the renovations himself. He’s in the process of ripping out all the existing plumbing, including septic, and another full bathroom will be added upstairs, plus a master bath off the largest bedroom.

Kinney’s neighborhood, officially designated the Lower Main Street historic district, is a hub of hipster activity in this bohemian Dutchess County city of 16,000 residents. Around the corner is Bank Square Coffeehouse, where great-looking Birkenstock wearers write screenplays on their laptops, and the unpretentiously fulfilling Tito Santana Taqueria, named for the famous Mexican wrestler. Both businesses operate from commercial structures of the same vintage as Kinney’s residence.

Located a convenient 75 miles north of Manhattan, and situated between Mount Beacon—actually two peaks in the Hudson Highland range—and the Hudson River, the city of Beacon is a 20th-century incorporation, born of two 17th-century settlements (Matteawan and Fishkill Landing) that grew together. Beacon was once a factory town that saw many period buildings demolished in the 1970s, but for the past two decades, architecturally interesting real estate bargains and proximity to nature have attracted families and creative types escaping New York. While Beacon’s gentrification remains uneven, the real estate prices are stable, and the quality of life is high.

Kinney plans on living in his house at least a decade and anticipates a handsome return on his capital and sweat equity. “I didn’t buy it to flip it, but I can’t say I won’t sell it in a decade or so, after I’ve really finished it,” he adds. “The way Beacon is going, it ought to be worth a mint by then.”

Scruffy Gentility

Right now, however, Kinney’s home is pretty scruffy. For example, the only functioning bathroom is downstairs. It had already been updated when he bought the house, if a tad haphazardly, in utilitarian white-on-white. There’s just one problem: at the moment, an old sheet, hung as a curtain, serves as the door—and it’s off the current dining area, where the preponderance of Kinney’s sparse collection of furniture is located. He doesn’t own much, yet, just a table, a few chairs, lots of tools, and an impressive collection of original sculpture and drawings, little of which is on display. Currently without a working cookstove, Kinney survives on takeout, banana smoothies, and foods he can heat up in an electric kettle.

“Not many people would have bought this house, because it needs so much work,” says Kinney. “Nevertheless, there was a bidding war when it came on the market, which drove up the price about $30,000, I was bidding against a lady banker from the city, but she backed off, finally. I had had my eye on this place for a while.”

The eldest of four children produced by a stockbroker and an artistically inclined homemaker, Kinney grew up in leafy, bucolic Boxford, Massachusetts. His nostalgic fondness for cozy but sophisticated small towns is part of what attracted him to Beacon. Kinney studied art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, earning a diploma from the latter in 1997. A tall, solid, amiable sort, Kinney’s known in the area arts community as a gregarious outdoors enthusiast, a man’s man. He likes to hike, and plans to eventually adopt a dog, now that he has a proper yard. “I don’t have a girlfriend either,” says Kinney. “But I’m dating, and it’s going really well.”

Home and Studio, under One Roof

“Having my studio and my home under one roof was a long-term goal of mine. I saved for years to make an investment like this—decades of perseverance and a clear intention,” says Kinney, sounding, perhaps, like his father’s son. “This house is zoned as two-family, but I’ve converted it back into a single-family residence. Right now my buddy Brian is renting a room from me—you know, a futon on the floor. It’s good for both of us and doesn’t cramp my style, at least not yet,” the artist says.

Kinney moved in the day after he got the keys. The first thing he did was install a tankless hot water heater, an improvement he regards as absolutely essential. He also replaced the inefficient conventional heating oil boiler with a cleaner-burning natural gas heating system, which he’s found to be more cost efficient. “I was shocked at how expensive it was to fill the 1,000-gallon oil tank—it cost almost $4,000,” says Kinney. The previous owner was a widower who worked for the prison system. An avid horticulturist, he didn’t do much to the interior, because apparently he liked “things the way they were,” says Kinney.

“It’s really educational, taking apart an old house like this. It might be a cliché, but they really don’t build them like this anymore,” he says, adding that all the crown molding throughout the downstairs is solid plaster. Kinney doesn’t much care for the old-fashioned mineral wool insulation; it’s very irritating to the skin.

After Kinney finishes the upstairs bathrooms, he’ll restructure the layout of the kitchen, informal living area, and dining room. “I’m going to make everything more open, with a breakfast island, but that may take a while. I’ve been crazy busy because I was picked up by Ethan Cohen Fine Arts gallery in Chelsea,” says Kinney. “I’m in a group show there called ‘Clear Vision’ at the end of July, and he showed my art at the SCOPE Art Fair in Miami in December.”

Kinney’s art studio occupies what was once the home’s front parlor. “The 10-foot-high ceilings, working fireplace, and great natural light make it right, plus, later, when people come to view my art, they’ll be able to check it out without venturing into my personal space.”

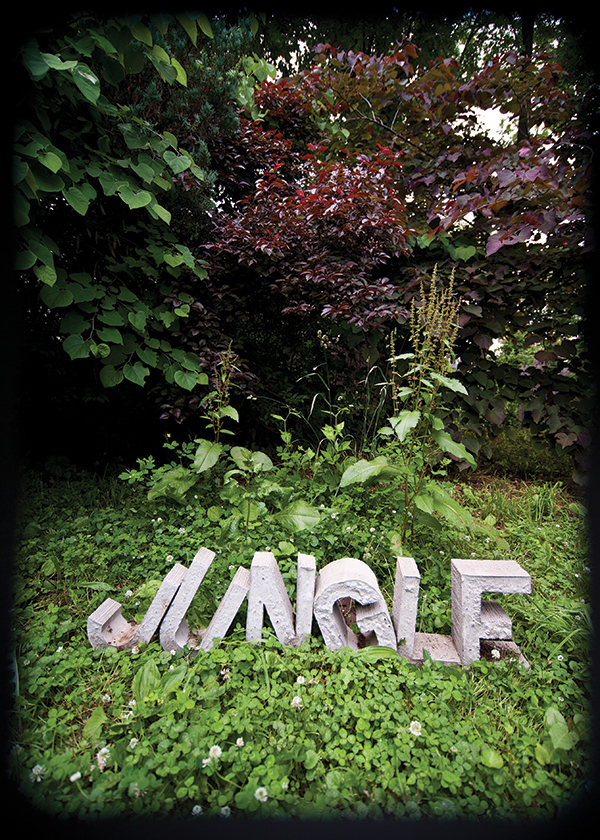

Kinney paints, draws, and makes sculpture; a few years ago he illustrated a book of poetry with a friend. He’s particularly proud of a series of oversize tools made of fine hardwoods that he made for a show in Beacon a few years ago. “The tools—a wooden hammer, an axe in ebony, and a speed square of black walnut—represent to me slices of my life as both an artist and a woodworker, and play with that continuity,” explains Kinney. “I’m juggling a lot right now. But this house is going to be my greatest work of art to date.”

This article was originally published in the July 2013 issue of Chronogram. It is reposted here with permission. All photos taken by Deborah DeGraffenreid

Read On, Reader...

-

Jane Anderson | April 1, 2024 | Comment A Westtown Barn Home with Stained-Glass Accents: $799.9K

-

Jane Anderson | March 25, 2024 | Comment A c.1920 Three-Bedroom in Newburgh: $305K

-

-

Jaime Stathis | February 15, 2024 | Comment The Hudson Valley’s First Via Ferrata at Mohonk Mountain House