A Family Portrait: Griffin Dunne’s Documentary on Joan Didion: Griffin Dunne brings his aunt Joan Didion to the screen in his new documentary

Upstater Magazine Fall 2017 | By Nina Shengold | Portrait of Griffin Dunne by Pamela Pasco

There’s nothing like a first audience to spike an actor/filmmaker’s blood pressure. Having starred in ’80s film classics An American Werewolf in London and After Hours, as well as, most recently, in Amazon’s hit TV show “I Love Dick” with Kathryn Hahn; producing such indie classics as Chilly Scenes of Winter and Baby It’s You; and directing a bevy of Hollywood features, Griffin Dunne has seen plenty of high-pressure screenings. But nothing compared with showing a roughcut of his new documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold to its subject and star. “We were side by side on the couch in front of my laptop,” Dunne recalls, speaking by phone from New York. “I don’t think I’ve ever been so nervous for any screening.”

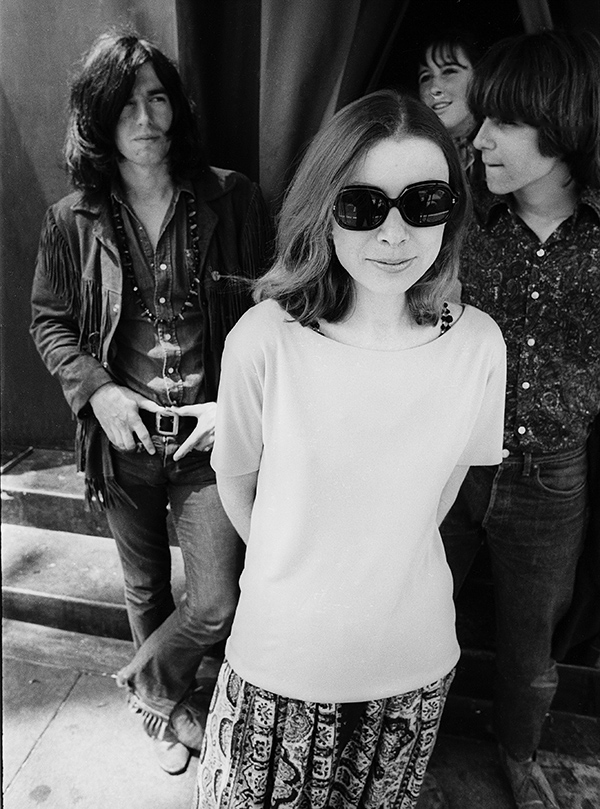

Julian Wasser photographed Joan Didion in the 1960s, when her essays focused on Californian culture. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Didion burst onto America’s cultural landscape in the mid-Sixties with the scorching force of a Santa Ana wind. She’s a writer’s writer, revered for her crystalline prose, incisive gaze, and unflinching honesty. Could the stakes be any higher?

Well, yes. She’s also Dunne’s aunt.

Their family connection and mutual fondness gave the filmmaker nonpareil access and trust. “I thought I was the only one in a position to ask and be given permission,” says Dunne; Didion had turned down several previous offers from documentarians. “So I asked her, and she said yes. And I thought, ‘Oh boy, here I go.’ It was an awesome responsibility.”

Their closeness informs the film’s texture. Dunne provides some narration and occasionally appears onscreen with his subject, who is now 82. And no other director could have asked Didion where she first heard about the Manson murders and gotten the answer, “In your mother’s swimming pool.” (With a reporter’s eye for detail, she recalls that Beatriz Dunne wore a Pucci swimsuit.)

Dunne’s father, the late writer/producer Dominick Dunne, was also a Hollywood insider. But his uncle, John Gregory Dunne, and his wife Joan Didion held a special allure, with their intertwined A-list careers, Malibu beach house, fast cars, and dark sunglasses. In a Kickstarter video for his documentary, Dunne calls them “the hippest couple on earth.”

“They opened up their social world to me,” he says. “I was always included in their parties, even when I was very young.” Dunne’s first directorial effort, Duke of Groove, in 1996, an Oscar-nominated short starring Tobey Maguire, was inspired by his having attended Didion and Dunne’s book party for Tom Wolfe while his parents’ marriage crumbled; Janis Joplin was among the guests.

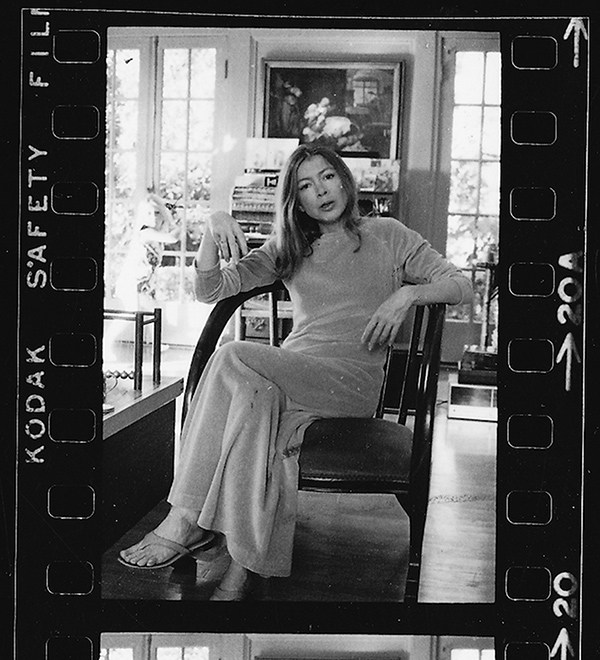

Joan Didion in her Los Angeles home in 1972. Photo by Julian Wasser, courtesy of Netflix.

After his parents divorced, Dunne moved to New York. He studied acting at HB Studios and started working in film, eventually forming the production company Double Play with Amy Robinson.

Nearly two decades ago, he bought a former dairy farm in Dutchess County. “It’s my haven,” he says of the rambling spread, which includes a swimming pond and small menagerie (dog, ponies, an ostrich), calling it “the greatest thing, outside of having a child, I’ve ever done.” His daughter Hannah, an actress, is now 27.

Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold will screen at this year’s Woodstock Film Festival; Dunne is a longtime member of the WFF’s advisory board and WFF screened his feature Fierce People in 2006. Executive Director Meira Blaustein says she began speaking with Dunne a few years ago about screening the film, which she calls “a rare, intimate, and much anticipated look at the life of his aunt and one of America’s most influential literary icons.”

After several festival screenings, Netflix will give the documentary a global launch on October 27. Netflix’s support capped a six-year process of raising money, gathering archival materials, and shooting interviews with Didion and some of her very articulate friends (Anna Wintour, Tom Brokaw, and Harrison Ford, among others). “I would shoot and then stop, go off and do other jobs, come back and put more money into it,” says Dunne.

Along with “I Love Dick,” those “other jobs” included recent roles in Dallas Buyers’ Club and “House of Lies.” Dunne also reread Didion’s canon in chronological order: early essays for Vogue, debut novel Run River, breakthrough nonfiction collection Slouching Toward Bethlehem; screenplays for The Panic in Needle Park, Play It As It Lays, and others with her husband; The White Album; Salvador; Miami; and National Book Award-winner The Year of Magical Thinking (also a Broadway play starring Vanessa Redgrave), a memoir of her husband’s death. Didion’s is a mountain range of a career, spanning multiple genres.

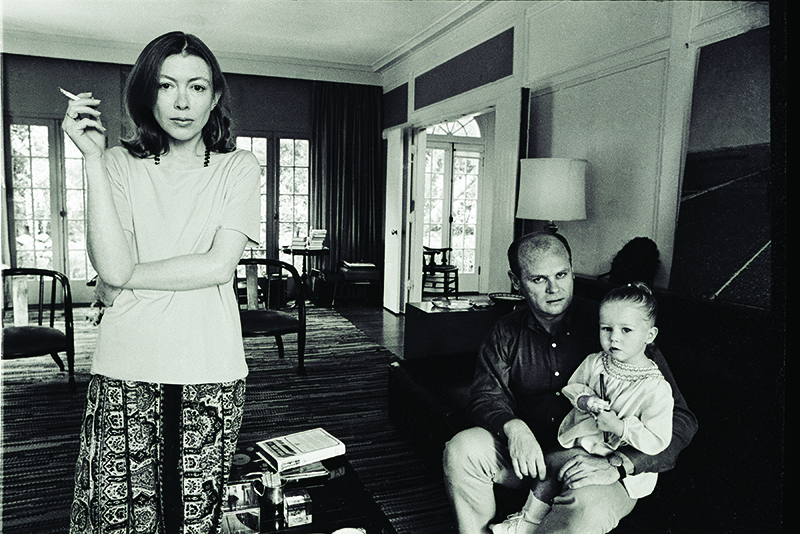

Joan Didion, with her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, and their adopted daughter Quintana, at their Los Angeles home in 1968, photographed by Julian Wasser. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

“In my darker moments, I thought, ‘What new things are people going to learn about Joan? She’s written everything about herself,’” Dunne admits. But even her nephew discovered surprises while filming: When Didion gets blocked, she wraps the manuscript in a plastic bag and puts it in the freezer.

There’s also the mesmerizing ballet of her hands, which sometimes seem to be combing invisible nets. “As you get older, things become more extended,” Dunne observes. “You look at these old TV interviews and she always did that, as if she’s grabbing thoughts out of the air, making associations physically as well as in words.”

Interviewing his Aunt Joan was “daunting.” He’d seen enough on-camera interviews to know “she does not suffer fools. If somebody asks her a stupid question, she can fix you with a look that will shut you right down.” He says Didion never declared any topic off limits, including the death of her adopted daughter Quintana, which she wrote about in her 2011 memoir Blue Nights. “She’s very much of the school of ‘That’s what I said, that’s what I wrote.’ No apologies, ever.”

Sharp-eyed and painfully thin, Didion appears both ruthless and vulnerable. Asked how she felt as a reporter seeing a five-year-old on acid, she says bluntly, “Lemme tell you, it was gold. You live for moments like that, good or bad.” But she’s anguished by the memory of finding drug paraphernalia in Quintana’s nursery after a party: “How could anyone do that?”

Dunne’s team also collaged archival footage of Didion’s subject matter—the ’60s counterculture, political turmoil—with period music and readings from her work. She’s watched every cut, “until about 10 minutes ago; we just changed a music cue,” Dunne says. “They’ll have to pry this film out of my cold dead hands.”

They’d better act fast. His next gig, in Italy, is to play Leonard Bernstein in the biopic Gore (Vidal, not Al). “Making a documentary is a high-wire act. You never know what you’re going to get,” says Dunne. “I can’t wait to shoot something with a script.”