Bike Like a Yogi: A Hudson River Cycling Trip

Upstater Magazine Fall 2015 | By Jeff Simms | Karen Pearson, Illustrations by Libby Vanderploeg

The Hudson River has shaped the lives of countless people. It’s the birthplace of U.S. commerce, the Hudson River School of painting, and the environmental movement, for starters. For me, the river means personal transformation. I’m a native North Carolinian, and, after living in Manhattan for two years, my wife and I moved to Beacon in 2009. Since then, our son was born in 2011, my wife beat breast cancer, and I changed careers. Having somehow survived these challenges, I feel it’s time for me to connect with the place I call home. So this past July, I biked the entire length of the Hudson River—340 miles—from Battery Park in Lower Manhattan to Henderson Lake in the Adirondacks, where the river begins. I’m a dedicated runner, but only a part-time cyclist, and I’ve never taken on a physical challenge of this magnitude. I’m approaching the ride as a type of yoga—off the mat. In Sanskrit, “yoga” means “union”—and this journey is wholly about forging a deeper connection to the natural world and myself. No single cycling route follows the Hudson directly, especially further north, where the river shimmies to the west and begins its crooked journey into the Adirondacks, so I’ve plotted my route as close to the river as possible.

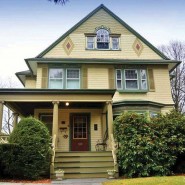

The 1.28-mile-long Walkway Over the Hudson isn’t just the longest elevated pedestrian bridge in the world, it’s also a popular meeting place

Day 1: Manhattan to Beacon (80 miles) The trip begins at Battery Park on a Monday morning. Coming along for the ride is my longtime friend Mike Mowery, from Silver Spring, Maryland, who I’ve known for 25 years. He’s the perfect partner. We’ve lived, traveled, and run races together, and he’s savvier about cycling and gear. I’m a low-tech guy: Basically, I’m going to get on my bike and ride it until the wheels fall off. I’ve been training for months. Nothing’s going to stop me. We push off at Manhattan’s southern tip and ride along Battery Park’s under-construction multi-use paths to the start of the Hudson River Valley Greenway, which is, surprisingly, nearly empty, and head north for 11 miles along Manhattan’s West Side. The George Washington Bridge and the Palisades loom in the distance. Cars speed along the Henry Hudson Parkway not far away. Although we’ve yet to leave the city, I already feel nature’s restorative power: My thoughts float past like the clouds overhead. In the Bronx, we head to Van Cortlandt Park’s 240th Street entrance, and onto the Old Putnam Trail, 1.5 miles of packed dirt along the western edge of Van Cortlandt Lake. We pass 13 pedestals of different types of stone, erected by Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt as an experiment to see which type weathered slowest and was therefore acceptable for the building of Grand Central Station. (In the end, Indiana limestone won for its cheapness, not its durability.) At the Westchester County line, the “Old Put” becomes the 7.5-mile, steadily inclining South County Trailway. Huge rocky outcroppings and lush greenery provide shade. Near Mt. Pleasant, the path crosses the Saw Mill Parkway and becomes the 22.1-mile North County Trailway, passing through Briarcliff Manor and Ossining. In the Hudson Highlands, breathing gets tough. I switch gears, literally and figuratively—deepening my inhalation as I climb Route 202, looking west across the river at sprawling, rugged Bear Mountain. Unencumbered by the trials of daily life, I’m free to connect with my surroundings. Like a yogi reaching for a pose that was once out of reach, I’m propelled forward with each exhalation. The last 10 miles, up Route 9D from sweet little Cold Spring to artsy, urban Beacon, are hard, but worth it. The Hudson looks like it goes on forever. The Highlands rise jaggedly from the glassy water. This is why I’m out here: to experience fully where I live.

Jeff, left, and Mike, right

Day 2: Beacon to Kingston (50 miles) After spending the night at my home in Beacon, we head to the Dutchess Rail Trail. The real trip begins today. We follow the paved trail for 13.4 miles to the Walkway Over the Hudson, a former railway bridge, which is bustling with lunchtime visitors. On the west side of the river, we pick up the Hudson Valley Rail Trail, a charming four-mile path from the hamlet of Highland through Black Creek Wetlands Complex to New Paltz, passing occasional abandoned railroad cars and former rail stations. It’s downhill into New Paltz for lunch, then we hit the 23.7-mile Wallkill Valley Rail Trail and head north to the historic Rosendale Trestle Bridge. Built in 1872, the 940-foot bridge-turned-lookout sits 150 feet above the Rondout Creek, offering views of Rosendale (a quirky village that thrived as a 19th-century cement-making center), Joppenbergh Mountain (whose dolostone was mined to make cement, and which, oddly enough, was coated in Borax, a powdered soap, in 1937 for a summertime ski-jump competition), and the world-famous rock climbing of the Shawangunk Ridge, marking the end of the Appalachians. Suddenly, the skies open. We hustle along the trail’s remaining 11 miles and into Kingston, arriving soaking wet and covered in mud. We’re camping tonight in the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s barn. We drop quarters into the barn’s pay showers before heading out to find dinner.  Day 3: Kingston to Albany (75 miles) We cross the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge early, under cloudy skies. The river is calm, but I’m not. I’m increasingly uncomfortable in my saddle and my gloved hands are numb as we head up Route 9G past Bard College and Tivoli and into Columbia County’s farm country. After heading back west across the shiny steel, cantilevered Rip Van Winkle Bridge, lunch in Greene County’s beachy town of Athens is rejuvenating, but by late afternoon I’m drawing on reserves again, while Mike is nursing a sore Achilles tendon. We’d planned to ride 10 miles off course to camp at John Boyd Thacher State Park in Voorheesville, 15 miles south of Albany, but we’re too spent to appreciate that the park is home to one of the richest fossil-bearing formations in the world. Instead, we follow Route 32 into the capital, to stay at a friend’s house in downtown Albany, giving us a break but maintaining the integrity of the ride. Day 4: Albany to Lake George (75 miles) After 10 hours of sleep, we push off on the Mohawk-Hudson Bikeway, both feeling better in all respects. The 86-mile trail meanders along a former barge canal connecting Green Island, Cohoes, and the Mohawk River, and includes both on- and off-street riding. When we reach the town of Wilton, on the outskirts of Saratoga Springs and the place where Ulysses S. Grant died after completing his memoirs, the scent of pines and the sudden appearance of long, steep, curvy hills tell me we’re nearing the Adirondacks. Business, so to speak, is picking up. We’ve got dozens of hills to climb between now and tomorrow. Ascending the first one, I think back wistfully to the Hudson Highlands—it’s a whole new ballgame up here. My thighs ache, sweat pours into my eyes and over my handlebars, and I’m moving so slowly it feels like I’m simply balancing my bike in place. We stop to refuel with an early dinner—give me the works!—in Lake Luzerne, where the Hudson squeezes into a narrow gorge and spills down Rockwell Falls. We’ve got 20 miles left to ride today. The afternoon drizzle turns into a steady evening rain, but I don’t care. My goal is in sight, and I’m inspired to see new places. We pass through Lake George village and coast two miles north to Hearthstone Point Campground, located right on the lake, where we’ll spend the night.

Day 3: Kingston to Albany (75 miles) We cross the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge early, under cloudy skies. The river is calm, but I’m not. I’m increasingly uncomfortable in my saddle and my gloved hands are numb as we head up Route 9G past Bard College and Tivoli and into Columbia County’s farm country. After heading back west across the shiny steel, cantilevered Rip Van Winkle Bridge, lunch in Greene County’s beachy town of Athens is rejuvenating, but by late afternoon I’m drawing on reserves again, while Mike is nursing a sore Achilles tendon. We’d planned to ride 10 miles off course to camp at John Boyd Thacher State Park in Voorheesville, 15 miles south of Albany, but we’re too spent to appreciate that the park is home to one of the richest fossil-bearing formations in the world. Instead, we follow Route 32 into the capital, to stay at a friend’s house in downtown Albany, giving us a break but maintaining the integrity of the ride. Day 4: Albany to Lake George (75 miles) After 10 hours of sleep, we push off on the Mohawk-Hudson Bikeway, both feeling better in all respects. The 86-mile trail meanders along a former barge canal connecting Green Island, Cohoes, and the Mohawk River, and includes both on- and off-street riding. When we reach the town of Wilton, on the outskirts of Saratoga Springs and the place where Ulysses S. Grant died after completing his memoirs, the scent of pines and the sudden appearance of long, steep, curvy hills tell me we’re nearing the Adirondacks. Business, so to speak, is picking up. We’ve got dozens of hills to climb between now and tomorrow. Ascending the first one, I think back wistfully to the Hudson Highlands—it’s a whole new ballgame up here. My thighs ache, sweat pours into my eyes and over my handlebars, and I’m moving so slowly it feels like I’m simply balancing my bike in place. We stop to refuel with an early dinner—give me the works!—in Lake Luzerne, where the Hudson squeezes into a narrow gorge and spills down Rockwell Falls. We’ve got 20 miles left to ride today. The afternoon drizzle turns into a steady evening rain, but I don’t care. My goal is in sight, and I’m inspired to see new places. We pass through Lake George village and coast two miles north to Hearthstone Point Campground, located right on the lake, where we’ll spend the night.

The Hudson River Valley Greenway, founded in 1991, is a network of multi-use trails on both sides of the Hudson River, creating scenic byways

Day 5: Lake George to Henderson Lake (60 miles) I’m so sore and exhausted that my pedaling no longer fully registers. We go 15 miles before stopping for breakfast in Warrensburg, where the bistro owner gives us complimentary cookies and grapes for the final ride. Back on the empty road, we head through pine forests, rustic towns, and farmland, climbing the never-ending hills to the sound of songbirds. By late afternoon, we reach Tahawus, a historic mining town. Two miles left! The Hudson shimmers through the trees. After passing the Upper Works, a dilapidated 19th-century iron-smelting plant, we pull into a parking lot and dismount for a short hike through the woods to Henderson Lake, named for one of the plant’s founders. Henderson Lake sits 1,800 feet above sea level on the side of Mt. Marcy, New York State’s highest point, and is fed in turn by a small tarn farther up the mountain—Lake Tear-of-the-Clouds, at 4,293 feet. The lake was discovered in 1872 but was named much earlier by Native Americans for its height and ever-present misty shroud. From there, the water flows to Lake Henderson via three tributaries: Calamity Brook, Opalescent River, and Feldspar Brook. While Lake Tear is indisputably the Hudson’s true source, it can only be reached by a treacherous climb that’s wet and muddy year round, making Lake Henderson the Hudson’s most accessible source. The lake is surrounded by thick forest, like a well-kept secret. Today ,it’s still and dark blue. Mike and I wade slowly into its cool, soothing water. Mission accomplished! After having climbed hill after hill, each one seeming that much harder than the one that came before it, I realize that I tackle these same “hills” every day. Some I conquer with ease. Some I struggle with. Others beat me down until I can barely move. Life is no different than these hills, and remaining calm and focused through the challenges on this trip means I can keep going in life, in all circumstances, as well. For now, I float on my back, grateful, as I stare high into the bright blue Adirondack sky.

For more information and maps for biking the Hudson River, check out HudsonThruBike.com