Chloe Caldwell | My Heart Was Still Beating

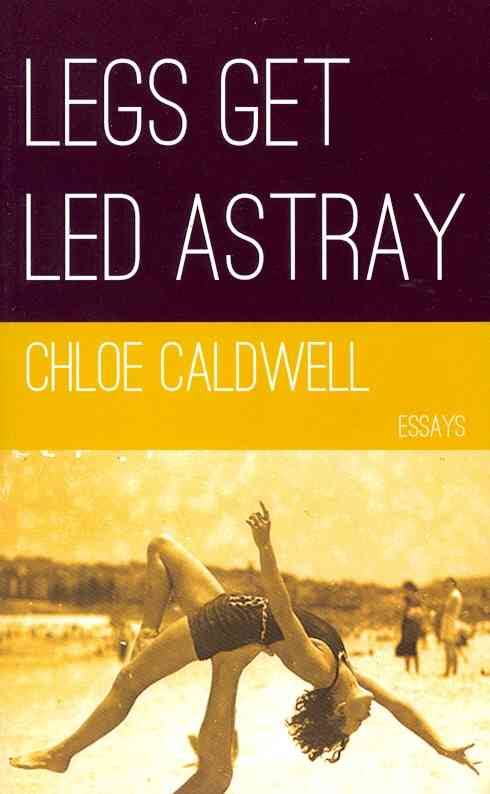

Chloe Caldwell | August 5, 2017This essay is excerpted from Chloe Caldwell‘s book of memoirs Legs Get Led Astray, published by Hobart Pulp. It is posted here with permission.

There were days when I preferred the boys I babysat to the adult boys in my life. To be a babysitter is to be part actor, part therapist, part housekeeper, part friend, part playmate, part athlete, part mom, part dad, part chef, part chauffeur, part waiter, and part saint, which I am not.

Take Caleb—the seven-year-old compulsive pizza eater.

“What do you want to do?” I asked him at the onset of our babysitting session.

“Read,” he said. “Read what,” I asked.

“Stephen King,” he said.

Sweet, I thought. His mom is an avid reader with a basement full of books. I read Nick Hornby and he read Stephen King in silence, and his cat was between us. A bowl of frozen peas rested on the ottoman. He loves those NOW CDs filled with the top-ten hits of the month so we were listening to Lady Gaga.

He lifted his round blue eyes, lowered his book, and broke the silence with: “Do you even know who Stephen King is?”

“ . . . Yes,” I said.

“Oh.”

“Why?”

“You just don’t seem like a person that would know who Stephen King is.”

Are you kidding me? I wanted to strangle his little neck, but he was right. I mean, how many Stephen King books have I actually finished? Zero.

I’m used to it. I got it all the time: “Do you collect

Pokemon?” No.

“Do you know what Bionicles are?” No.

“Are you good at drawing robots?” Definitely not.

“Have you seen Star Wars?” No.

“Did you read the Harry Potter books?” Hell no.

“You don’t know a lot of stuff.”

“I know.”

“Why?”

“Why what?”

“Why do you know?”

“Why do I know what?”

“Why do you know that you don’t know a lot of stuff?”

“I’m very aware of my strengths and weaknesses.”

“You’re not very good at football.”

Then Caleb asked me how many pieces of pizza I was going to eat, and I said one, and he said do you promise, and I said no, and he said can you please promise to only have one because I want to eat as much of it as I can.

So I ate one slice of pizza and he ate four and got a stomachache while we watched School of Rock on television. When the movie was over he asked me if I could draw him a peace sign poster. I said yes I could, if he would go to bed right afterward. We went upstairs and I hung the peace poster on his door and we crawled into the bunk beds—him on top and me on bottom. We read more, which was great, but he kept asking me what page I was on, how much have I read, and when I told him—he smirked. When I heard his breathing get heavy and steady I went downstairs to masturbate.

Let me be frank with you: I’m not the world’s best nanny.

I have not won any awards or ribbons at it. I go to the bathroom when I don’t even have to go to the bathroom to kill time. I am distracted. I am sarcastic. I do not listen. I am uptight. I am selfish. I am tense. I text while I drive. I make promises I don’t keep. My chocolate chip cookies are spongy. I am impatient. I over-explain. I am existential. I try to tell them nothing matters. I tell them about cremation. I once asked them where they wanted to be cremated. The toy store, they said. They wanted to be cremated at the toy store. I told them they can’t do that. It has to be outside. The toy store parking lot, they decided.

But for some reason the kids liked me. I made them laugh.

I have always been able to make boys laugh. I am blunt. I make jokes. I will get on the floor. I play along. I play tag. I buy them ice cream. I bring them gum. I try to remember their birthdays. I laugh a lot. I let them win. I let it slide when they say the words: crap, freaking, sexy.

Despite the competitive pizza eating and reading, Caleb and I did get along. He has long bleach-blonde hair and gets mistaken for a girl often. He’s chubby from all the pizza and he plays soccer and football. He’s constantly trying to make money. He’s either selling lemonade or making bracelets.

Or he’ll have some master plan—like having a bake sale for Haiti but keeping most of the profits.

We were driving to the beach one morning with the windows open and listening to Carole King’s “Where You Lead.”

“Hey Chloe?”

“Yeah?”

“Last night I had a dream you died.”

I glanced in the rear view mirror. He was staring out the window.

“You did?”

“Yeah. It was weird.”

“Did you wake up sad?”

“I don’t know. My heart was still beating.”

“Well, that’s good.”

“Yeah. People don’t die until they’re really old, right?”

“Usually.”

“Chloe? “Yeah?”

“My mom has cancer.”

“I heard. I am so sorry.”

“I want the cancer to die. DIE, cancer DIE!”

“Me too, Caleb,” I said, for lack of a better response. I felt inadequate.

He was quiet and I thought the conversation was over, but then he thoughtfully asked, “Do you think it would have been better for me to be a baby when she got cancer or now?” My heart clenched.

“I think it would be hard either way. But maybe now; because you are smart and can understand it.”

“I’m not that smart. Actually, yes I am.”

Caleb’s mom described her son as a bull in a china shop and said she couldn’t believe I could get along with him. “My son loves you,” she told me. “He said to me, ‘Mom, I told Chloe something and she laughed so hard she put her hands on the table and threw her head back.’ ” I love him too. It’s true that he was the most argumentative boy I had, but I’m okay with argumentative. It felt like hanging out with my own mom. He was also the oldest boy I took care of—he’s eight—so he was the most helpful. I have been lost with him on highways for hours at a time, supposed to be taking him to the Museum of Flight, and he always figures how to get to I-5 South if we are on I-5 North before I can and for that, I am grateful.

I slept over at Caleb’s house for three nights in a row one week. His parents went on their fifteenth anniversary getaway to a cabin in Canada. He woke up at six in the morning and came into the bedroom I was sleeping in and he asked if he could go watch TV. Yes, go, I told him. At six thirty he came back into my room and asked if he could have pizza for breakfast, and I wanted to say, yes, heat it up in the microwave, but instead I got up and made us cheese omelets and lemon tea with milk and sugar and he flipped back and forth between Scooby-Doo and the History Channel. Then I brought him to his Montessori school driving a green Jeep and I tried to imagine this as my life and I wanted to scream.

That night, after Caleb went to bed, I was walking back out to the living room to watch bad TV and I saw his lunchbox on the counter. I walked right by it, but I knew that I was working, and that I should empty it out, clean it and pack his new lunch. I didn’t want to. Just the thought of it exhausted me. Bored me. But then for a second I pretended he were my son, and I got sort of excited. I think if he were, I would become obsessed with him. I would be like Anne Lamott, constantly writing about him (I feel sorry in advance for him). I would want him to experience love. I’ve always wanted a son. My mom used to laugh because I would go to her classroom where she worked and I preferred the boys to the girls. I have always preferred boys to girls. I opened his lunch and examined it. I saw that he did not eat his peanut butter sandwich and that he only had a few bites of his apple.

The next night, Caleb and I went out to dinner at a place called Hales and split the nachos. I told him I needed a beer.

I don’t usually get up at six thirty and I needed to take the edge off. This is why Caleb is great, he was like: “Oh, do you like hops? My dad drinks the Super Goose I.P.A. because it’s really hoppy. You should get that.”

And I did. God bless Caleb.

We both loved the same radio station, The Mountain, and as we cruised home through downtown Seattle, we were happy. “Jammin” came on and he said, “I know this song! Turn it up! I know this song! Do you?”

“Yep. It’s Bob Marley, dude. Everyone knows this song.”

“But do you even know where Bob Marley is from?”

“NO. WHERE?”

“Jamaica! He’s from Jamaica, mon!” We cracked up and I turned the music up and for once I did not get us lost.

Things were not always that easy. Babysitter is a vague word, an obscure job. I am starting to think it is as real as a job can get—taking care of another human being.

When I lived with Caleb for those three days, he had a soccer game I took him to. Afterwards, he was fooling around with his friends and the ball hit him in the face, hard and fast, crushing his nose cartilage, and he cried like a baby in my arms while his nose turned blue. Another time, his little brother was really sick and I was instructed over the phone by his mom to get a stool sample from him, which I did, and then I had to drive the two crying and arguing boys to the emergency room with a plastic container of shit in my hand. And once I forgot to pick Caleb up at school. Enough said. He was good-natured and readily forgave me and later I was not surprised when he was voted class humanitarian of the first grade. I hugged him tight and apologized one hundred times and he hugged me back but rolled his eyes and said, “You don’t have to hug me, jeez.”

Then there were the moms.

I loved the moms. The moms gave me whole wheat rolls, mangoes, chicken, homemade Indian food, weights, jumpropes, toilet paper and cardio DVDs. One mom gave me $300 for a bike. One mom gave me an Ikea bed frame. The moms count calories and pawn junk food off on me. The moms come home drunk and can’t find their checkbooks. One mom came home, lay down on the floor, and told me she was wasted. She asked me about myself. “You moved here from New York? You’re so adaptable!” she said. “You’ve done more than I’ve done in my whole life! Do you blog about it?” The moms tell me they were in my position not too long ago. The moms told me that babysitting is the best birth control in the world. They told me they remember what it was like to have roommates. They told me I can borrow any of their Anne Lamott and Pema Chödrön books and stay at their houses when they are away and watch On Demand TV. The moms usually overpaid me. The moms had thousand-dollar laundry chutes.

“You get what you get and you don’t get upset,” one mom explained. “That’s what you have to tell my kids.”

It became my mantra. That and, “Don’t turn a good thing into a bad thing.”

Here’s the thing about kids: they do not care if you have to go to the bathroom. They do not care if your head hurts. They do not care if you need to make a phone call, if you are starving, if you can’t find your wallet or your keys or if you are hung over. They do not care if you are experiencing the worst menstrual cramps of your life. They do not care if you are speeding and there is a cop behind you. You must be there for them. They are not there to be there for you.

Like the time I was slicing an apple and the kids were in the other room and I cut my finger, getting red blood all over the apple and the counter and I yelled, “Shit, guys!”

Expecting help. A little compassion. A little direction to where the Band-Aids were. But no, they just laughed a little and ignored me.

It’s hard for me to have my shit together for the kids all the time.

The other boy I babysat on a regular basis was an energetic brown haired boy named Bradley. The first time I met him I said, “Hi Bradley, it’s nice to meet you.”

“Hi,” he said, “I just got my hair cut, and she did NOT do what I asked her to do, I’m going to sue her.”

“Let me see.” He whipped his hat off and he looked like John Travolta.

“It’s not that bad,” I told him.

“I asked for bangs and she did not give me bangs.”

“She just didn’t style it right. You gotta mess it up a little.”

“Mess it up? You’re a maniac!” he told me.

We were playing Star Wars once and while crouched behind the couch, Nerf guns in hand, he looked at me and whispered, in earnest, “I’m a cancer survivor.”

“You mean in the game?”

“No, in real life. I’m a cancer survivor.”

Later, I spoke to his mom about it and she told me he was born with leukemia. Then she told me, “Bradley thinks you are more of a buddy then an authoritarian.” She didn’t sound happy about that.

Bradley and I were close. He was the only person to give me flowers for my birthday. He made me necklaces and gave me stones that he calls “gems.” We danced around to his Alvin and the Chipmunks CD, made up a secret handshake, and rode our bikes into town to get smoothies and play at the water park. His favorite toys were these things called Bionicles (which I’m still confused about—I guess they are a form of a robot created by Lego). I admired his creative mind—he could make up interesting games of pretend all day. But in every game, he would “win” out of nowhere because he had an invisible gun, or I was standing in hot lava, or the ball was actually a bomb and it exploded while I was holding it. It’s grating after a while. The boys always want to win. If I didn’t let them win they’d get tears in their eyes: “It’s not fair!”

One spring afternoon, Bradley told me he was in a forcefield and that it was impossible for me to “get him,” no matter what I did. He said this with complete pride, mockery.

“Then what am I supposed to do?” I asked, standing by the fence. I felt helpless.

“Well you still gotta try to get me. But remember—you’re part Godzilla, part zombie, and part baby.”

“Okay.”

“So be it.”

“How?”

“Make grrrrr-ing noises and stuff.” “Okay.”

I hated my job at that moment. It’s easier with the younger ones. I can give them candy or a piece of gum and boom, they are high on life. But the seven-year-olds are intense and it takes more effort. It takes being good at acting part Godzilla, part zombie, and part baby. Eventually the game ended, and I thought I did well: I made him laugh by growling and moaning and falling down and throwing rocks at the ground, walking with my arms out like a zombie and saying “goo-goo gah-gah.”

After dinner we went outside to have a pogo stick competition. All kids are narcissists, which makes my job easier, because all I have to do to get them excited is tell them that I will make a video of them, or take a picture of them on my phone, and that kills time pretty well. I can’t usually get more than three consecutive jumps on the pogo stick. He can get six.

“Can you make me a fruit and cheese plate?” he asked, in a good mood, because he won.

“Sure!”

Bradley and I sat on the couch and watched Tom and Jerry and ate cheddar cheese, apples, and clementines. He moved close to me so that half of his body was on top of mine and during the funny parts he looked at me to make sure I laughed.

The boys never want to brush their teeth. They all say the same thing: “Imagine if I brushed my butt with this! Dare me? Dare me!” (The girls I babysit have mechanical toothbrushes that play a tune every few seconds—reminding you to brush your front teeth, then the side teeth, then the back teeth. They like to explain their toothbrushes to me. Show them to me. Ask me what mine looks like. If it’s electric. It’s not. The disappointment is obvious.)

After he “brushed” his teeth, we went into his bedroom and he got all weird and self-conscious about his penis. He changed into his pajamas and I waited in the hall.

“Don’t look!”

“I am not looking.”

“Okay, fine, you can look.”

“I am not looking.”

To abide by his parents’ rule, we have to read two books, one each. He read If You Give a Pig a Pancake and I had to read Star Wars. I hate Star Wars so much. I just don’t understand it. There I said it. But that’s what he always chooses and I get so bored reading it. As though I am not even hearing myself when I read. But my mind is not anywhere else either. Just going through the motions. It’s weird.

My point is: I was so bored reading it, so I used the same tactic I do when I am bored reading anything. Just to entertain myself, I pretend I am on stage. So I started reading really theatrically, and he loved it. I mean he fell over himself laughing. But after I did that once, I had to do it every time. “Can you do it in that funny way?” he’d ask.

When I’d been babysitting Bradley for just under a year, we stopped getting along so well. It was a lot of my fault. I got depressed, distracted, disengaged, the way I have in other relationships. When he wanted to play something, I made excuses, and when I did play, I half-assed it.

“You’re no fun anymore!” It broke my heart. One night at dinner he was acting particularly out of character—really rude and whiny.

“What is your problem lately?” I snapped from the sink.

“You have no idea how hard my life is!”

I walked over and pulled up a chair. “What do you mean?”

“I have to clean up all the time. I have to vacuum after every meal. I have to buy my own Lego sets. You don’t know what my mom is really like. If you lived with me, you would see what it’s like when you’re not here. My mom thinks I’m dumb. When I do some stuff, she doesn’t love me.”

“I think maybe you are sick of being home with your mom all the time. School is starting soon, and you’ll have fun in second grade. I did.”

“I hate school. I just want to stay home all day and play with Legos and watch TV.”

I reminded him that he liked writing stories. He was always writing them in notebooks. I suggested he get a journal and write down his feelings about his mom in it, and he seemed satisfied with that I felt horrible for the kid. That image of him so distraught with tears falling into his plate of cold chicken nuggets stuck with me for days. I couldn’t believe how the relationship had changed and I remembered what it was like when I’d first started babysitting, the previous October. He liked me to lie with him until he could fall asleep.

“Can we talk?” he’d whisper, his head on my shoulder.

“For a minute,” I’d say, and he’d go into long detailed play-by-plays of what he’d seen on America’s Funniest Home Videos.

“What are you afraid of?” he asked me one night and then waited, listening.

The question hung for a minute, because I was trying to figure out how to be honest but also not scare him. All I could think of, though, were extremes.

I didn’t want to tell him I am scared of a rapist or a murderer jumping out of an alley way and killing me each night, so I walk with my keys with one in between each finger and I feel safer that way, knowing I could punch them in the eye, though I don’t ever want to have to. I didn’t tell him that I’d just read The Highly Sensitive Person in Love and found out that I have a fear of engulfment. I didn’t tell him I am scared of being poor forever. I didn’t tell him that every day when I ride my bike I am sure I am going to get hit. I didn’t tell him how afraid I am of my parents dying and how even though they are both relatively healthy, tears well to my eyes at the strangest of moments, while I am on the elliptical, making coffee, or walking to the post office, and I envision myself having to fly home to my father’s funeral and it makes me want to crawl into a closet and bawl.

“Dogs,” I decided to say, half whispering. “I’m a little bit afraid of dogs.”

But he was off the subject already, propped up on his elbows saying, “Wouldn’t it be cool if . . . ” And he was talking about Legos in a language I’d never understand. We lay there a little longer and his skinny leg was flung over my leg and as he was on his way to dreamland he mumbled, “You know what?”

“What?”

“I’m a little bit afraid of dogs too.” “Yeah?”

“Yeah. I really am.”

When his breathing deepened, I gently pried his head off of my shoulder and tried to sneak out of the bed in one swift yet quiet motion. I picked up my shoes and tiptoed down the hall.

The next morning, I arrived for work at nine. Bradley answered the door, averted his eyes and said, “Hey man, what’s up?” acting like nothing happened—like we didn’t just lie together in a dark room telling one another our fears.

Just like a man would do.

A year later, I found myself telling Bradley I’d be moving back to New York.

“Why?”

“New York is where my family and friends are, and I miss them.”

“Fine. But you lied. You said you would stay in Seattle for a long time.”

I told him I was sorry if I said that and that sometimes things change. I told him we could write each other letters. We walked home in silence. Bradley wanted to watch Animal Planet. The TV wasn’t working and he went behind it and started messing with the wires.

“Can you get out from there, please? You could get electrocuted.”

“Why do you always have to think of the worst possible thing that could happen?”

I smiled.

“Good point. I don’t know. I guess because you are not my kid, and I don’t want to tell your mom that you got electrocuted. Also, if you got electrocuted, I would die.”

“No you wouldn’t.”

“Well, my life would be over in a lot of ways.”

“Yeah. I’d miss me, too,” he said, smiling.

At nine, I told Bradley it was time for bed.

“Can I write?” He asked. “I keep a secret diary now, like you told me to. It’s so awesome. I have to write in it every night. I hide it from my mom. I keep it under the mattress on the bottom bunk.”

I was touched, and told him of course he could write, that I used to hide my diary from my mom under my mattress too, and to call me if he needed me. An hour later, he yelled for me. I went in.

“Remember how I told you I wanted to stay home and play Legos and watch TV all day?”

His eyes were glazed over, the same way mine get when I’m inspired with ideas about writing.

“Yeah.”

“I actually want to force my dad to make me a treehouse, and I want to write stories and comics in it all day.”

“I think that sounds like a great idea. Listen, I’m not going to tell you to stop writing, but it’s ten at night and your parents are going to be home soon. So when they’re home shut off that light and pretend you’re sleeping.”

“I’m just going to write a few comics now.”

“Okay.”

“I might call you back up to show them to you, okay?”

“Okay.”

But he didn’t. And at close to midnight I walked upstairs to peek in his room. Fast asleep. I felt nervous as I lifted the bottom mattress up a little and reached for his black diary with a brass lock that was not locked. I opened it and giggled at pictures he’d drawn of robots and aliens. Then I saw this:

The zoo and acwaream

After scool one time I went with my babysiter to the zoo it had cracadils. And snaks too. Evin a fuyuw zebras too. Than we went to the acwareum too. Had sharks. I lauv sharks a lat. And a lat of fish. I thot this might be a good goodby preysent. Il miss having her because I had a lot of fun with her. I hope she has a nice day at Nuwuawrk.

I pulled my knees into my chest and started to cry. Then I tore the piece of paper from the diary, folded it in four, put it in my back jeans pocket and quietly walked downstairs to read and eat ice cream.

Read more from Chloe Caldwell in the summer 2017 issue of Upstater.