Get Grounded: When Amy Hepworth, farmer and cult hero, questions organic orthodoxy, it’s time to pay attention.

Upstater Magazine Summer 2017 | By Susan Piperato | Photos by Hillary Harvey

n the food world, farmers, unlike chefs, don’t become celebrities—unless they’re Amy Hepworth. The outspoken organic farmer grows more than 400 types of vegetables and fruit on a 400-acre farm in Milton, across the Hudson River from Poughkeepsie. She has won a huge following in New York City by supplying produce to the Park Slope Food Coop, Whole Foods, and a long list of high-end restaurants.

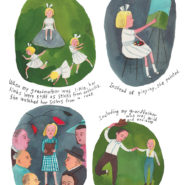

Part of Hepworth’s star status arises from her pedigree: She’s a seventh-generation farmer on land cultivated by her family since 1818. But she’s also a larger-than-life personality: passionate but practical, philosophical but blunt, frequently prescient, and openly emotional. She often mentions the need for the public to “hear the farmer’s cry for help.” But her demands to be heard are well earned. She’s hoed a tough row, so to speak, from the get-go. Born on the farm as one of five kids, she was driving tractors at nine and trucks at 12, pitching in to help her mother after her father took off following a fire that ruined one of the farm’s packing facilities. (Hepworth’s twin sister Gail, a former biomedical engineer, joined the farm as head of production in 2009.)

Hepworth has been vocal about many issues, including advocating for living wages for farm workers, decrying the defunding of agricultural research, preferring organic alternatives to pesticides and fungicides, championing hundreds of rare and fussy heirloom varieties (including Shiro plums), and promoting the eating of maggots and insects. (Sometimes that’s what happens when we don’t use chemical pesticides; besides, they’ll make good protein sources if there’s a worldwide food shortage someday.) But most famously, she supports “hybrid” farming, based on organic principles but with flexibility when it comes to technology, that eschews what she calls the “two-party system” in which “‘organic’ is seen as ‘good’ and conventional is ‘bad.’”

In December 2015, the Cornell Alliance for Science website posted Hepworth’s op-ed piece on hybrid farming. “The organic movement was successful in changing the way the agricultural industry operates,” she wrote. “But the time has come to release ourselves from the tyranny of the label—taking its valuable lessons and evolving beyond organic to create the safest, most ecologically, economically, and socially just agricultural system possible. Advances in biotechnology are a natural fit to meet the demand of the population for sustainably grown food.”

Although Hepworth initially got a lot of flack for her views, she’s won the farming industry’s respect. The Cornell Alliance for Science named her farmer of the year in 2016; and she’s been profiled by New York magazine, the Washington Post, and the New York Times.

Lately, Hepworth is talking about how arable soil—dirt that contains enough nutrients to grow high-quality food—is disappearing. Six inches, or 150 millimeters, is the minimum topsoil depth required for farming, according to FEWresources.org, a website devoted to the study of food production, energy, and water. Replacing just one inch—25 millimeters—of eroded topsoil takes 500 years. From that perspective, arable soil is a nonrenewable, endangered ecosystem.

“We can’t live without the sun or water, right? Well, we can’t live without soil,” Hepworth says. “Soil, when it’s complex, gives plants the right nutrients. But we’ve degraded our soil in agriculture, and we’re losing our soils worldwide. We’ve created very productive seeds, but we’re not getting the seeds’ natural genetic potential, and we’re losing our efficiency, because our soils are losing their organic material.”

People assume soil is a renewable resource that can be depleted and replenished by decaying organic matter, but that’s not so easy, says Hepworth. A 2015 study by the University of Sheffield’s Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures estimates that nearly 33 percent of the world’s adequate or rich food-producing land has already been lost, and that soil is steadily disappearing at a rate that’s outrunning the pace of natural processes to replace it.

“We’ve lost two billion hectares of soil, and there are only one-and-a-half-billion hectares left [on earth],” says Hepworth. “We have a growing population to feed”—by 2050, she notes, there will be 9.5 billion people on earth—“and if we continue [to erode soil] at this rate, it’s suicidal. A basic human right is to eat. We have problems now feeding people—people are malnourished and hungry on this planet—and it’s going to get worse. We need more intelligence, more science.”

In the mid-20th century, the ironically named “green revolution,” turned agriculture into an industry, says Hepworth. Farmers utilized chemical fertilizers and machinery, and farms expanded into multinational businesses to produce more food, faster and cheaper. “When the ‘green revolution’ came, it fed a lot of people cheaply, and we got ourselves into a situation. We were inherently unaware of what was gonna happen,” she says. “Now we have to figure out a way to prioritize feeding people healthy food, with nutrients, and be environmentally sound about these things. It’s an obligation.”

When Hepworth took over in 1982, after earning a B.S. in pomology (the science of growing fruit) from Cornell University, the farm was a commercial apple producer. She began by infesting apple trees with mites to attract the mite’s predators as natural pesticides. Much of the apple crop was lost in the process, along with “hundreds of thousands of dollars,” says Hepworth; her family nearly fired her.

Nevertheless, she persisted, and successfully transitioned the farm to more holistic operations. In 1983, she began selling produce to the then-260-member Park Slope Food Coop. Today, the coop has 16,000 members, and Hepworth supplies it with 111 types of vegetables (accounting for about 80 percent of her vegetable sales), and 53 kinds of fruit. Angello’s Distributing brings her produce to regional coops. Whole Foods also sells it, and Mike’s Organic Delivery delivers it to clients in Westchester County and Connecticut and farm-to-table restaurants in New York State. Locally, it is served at The Would in Highland and sold at Heart of the Hudson Valley in Milton.

In 2009, with the tomato crop infected with late blight, the air-born fungus that led to the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s, Hepworth sprayed a copper-based fungicide. Copper is one of very few blight fighters available and the only organic one, but it doesn’t break down, thus permanently impacting soil biology—which Hepworth doesn’t take lightly.

She’s decreased energy consumption through solar power and geothermal heating and cooling systems, and raised wages for over 200 farm workers. “I’m not the easiest boss, but we grow together on this farm,” she says. “Things are coming together because we’re together as a people. Imagine you have 100 people working together to accomplish something, how much better that feels than to have one person taking the profit for themselves. Then it means nothing. It’s a great ride we’re on here. We’re a happy farm.”

Yet despite expanding the farm from 50 to 400 active acres, offering increasingly popular produce, and achieving national fame as a farmer, she’s only recently made a profit. “I have a very unusual principle around money. I believe it to be currency, and it’s always moving,” she says. “I don’t have retirement. I only have debt. I can borrow crazy amounts of money I couldn’t even pay off if I wanted to in my whole lifetime. I don’t make money, but people think I make money. I just distribute it. It comes in and goes out again.”

In the end, the soil matters most. “Agriculture is the machination of the natural ecosystem,” Hepworth says. “Every time I go out on the farm, I’m actually hurting the land. Dropping ploughs, kneading soil, planting crops is unnatural. But we can figure out a safer way to do it.”

So, what’s Hepworth doing about all this? She is deeply influenced by French agronomists Claude and Lydia Bourguignon and their “manifesto for endurable agriculture.” “We have to learn from others,” she says. “[The Bourguignons] have been doing it for 35 years. They’ve dug 12,000 holes all over the planet to understand soil. They have a lab, and I’m sending some of my soil there.” She publicly laments the lack of both American agronomists and soil research—including at her alma mater, Cornell, which has been defunded by 70 percent. “The soil is the biggest biochemical energy in the universe,” she says, “and we don’t even study it properly.” She sits on the board of directors of the Hudson Valley Research Laboratory, in Highland, a farmer-owned, regional research facility in partnership with Cornell. And she’s constantly reading antique agricultural books. Currently, her favorite one is from 1856. “I like to go back in history and compare,” she says. “We live in an intellectual time, but it isn’t the only one.”