Requiem for a Sense of Place: Jeremiah Moss on Gentrification

Upstater Magazine Fall 2017 | By Sari Botton | Photos by Hillary Harvey

Gentrification Stirs in Kingston

It’s a muggy Friday afternoon in late August, and I’m showing New York City writer Jeremiah Moss around Uptown Kingston.

Dashing between raindrops, I take him to commercial properties that have recently been sold to landlords from New York City for way, way above appraised value. On the way to the Cioni building, a 22,680-square-foot former school built in 1841, we walk past other brick buildings, beautified with murals painted during Kingston’s annual O+ art and music festivals—The Hobgoblin of Old Dutch by Matthew Pleva, Bilancia by Kimberly Kae, Artemis Emerging from the Quarry by a painter who goes by the name Gaia.

When I mention that a bid of $4.23 million was recently accepted for the Cioni—more than twice the next highest bid—Moss’s jaw drops. Then we stop in front of a storefront with its windows papered over, the former site of a small, independently owned guitar shop that relocated after the building’s new owner raised the rent by 67 percent.

“The rent went up how much?!” Moss asks. I repeat the number. His surprise is, well, somewhat surprising, considering who he is.

A Cautionary Tale

Moss is well known among New York City dwellers and ex-pats alike for his blog, Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, AKA The Book of Lamentations: A Bitterly Nostalgic Look at a City in the Process of Going Extinct, where, since 2007, he’s chronicled the shuttering of one New York institution after another. Several times a week, he laments the rising astronomical rents killing favorite restaurants like Midtown showbiz canteen Cafe Edison, nightclubs like CBGB, watering holes like Mars Bar, and mom-and-pop stores like Pearl Paint.

He started #SaveNYC, “a grassroots, crowd-sourced, DIY movement to raise awareness and take action for protecting and preserving the diversity and uniqueness of the urban fabric in New York City,” according to its website, SaveNYC.nyc—a place where people can post videos and photos about businesses that need support in the face of rising rents.

Moss organizes protests, most of which he himself sits out because, as a psychotherapist, he has long cloaked his identity. In the June 26, 2017 issue of The New Yorker, Moss revealed himself to be Griffin Hansbury, a psychotherapist and a transgender man, but for all things Vanishing New York, he still prefers to go by his pseudonym, which he borrowed from the protagonist of a novel he wrote while pursuing an MFA in creative writing at NYU.

I’ve read in other interviews that the character’s voice is “cranky,” or “grumpy.” “Is your character’s voice different from yours?” I ask.

“Not really,” Moss says. “But it’s sort of a distilled version of mine.”

He also frequently gripes publically—on his blog, in newspaper op-eds—about urban planning policies that privilege corporations over people, and give tax breaks to major chains taking over the city’s landscape. “My activism is largely discursive,” he says. “I do it through writing to raise awareness and hopefully inspire others to action. I think that has happened—or people tell me it has. I know my writing, in particular about policies, has inspired some politicians and other activists. So that’s something.”

The subject at the heart of all of his writing is neoliberalism. “I’m such a pain in the ass about neoliberalism, because I love talking about it,” Moss says, clarifying that there is actually nothing “liberal” about it. He defines neoliberalism as “an economic philosophy that is about redistributing wealth and other resources from the bottom to the top—privatization, deregulation. It’s how we got here.”

Just two years prior to Moss’s blog launching, in November, 2005, my husband and I moved to the Kingston area after a housing court battle ended with us being evicted from our rundown, sprawling, under-market-value apartment in the East Village. During our last years in the city, we had noticed a dramatic acceleration in the frequency with which our favorite haunts were closing, thanks to rapidly rising rents. Our own rent had more than tripled in just one year, once our landlord received landmark status and realized the building wasn’t rent stabilized. It was like gentrification on steroids.

Or, to use a term Moss coined, we were witnessing the effects of—and we were casualties of—hypergentrification.

Vanishing New York supplied the balm for my broken New York City-expat heart. I read every post, and then, with the advent of Facebook, noticed that many of my friends were reading and reposting Moss’s blog postings, too—both the ones who were still hanging on in the city and my new community of fellow New York City-expats in the Hudson Valley.

Vanishing New York—A Postmortem

Now there’s more Moss for his many fans to read. In August, he published Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost Its Soul (Dey Street Books). It’s not your typical blog-to-book proposition; this is not a compendium of ancient blog posts. Instead, it’s a beautifully written, thoughtful, and comprehensive postmortem on what happened to the city to which Moss had excitedly moved to over 20 years before, from a working-class Boston suburb, to attend graduate school. The book seamlessly combines historical reporting, economic and social theory, and bits of memoir.

I decided to bring Moss to our much smaller city for an in-conversation book event at City Hall so that we could discuss the mechanics of what happened in New York City, and, I hoped, use Moss’s feedback to begin to strategize a defense against hyper-gentrification here. As Kingston residents, we want to see our long-depressed city revitalize and grow, but in a sustainable way, without the ill effects of hypergentrification leading to the displacement of writers and artists like me, people of color, and others who are disadvantaged and have been marginalized.

But before Moss’s reading and talk are to begin, I squire him throughout Kingston—first on foot through Uptown; then by car through Midtown and Downtown; and finally out to Kingston Point and the Hutton Brickyards, where an upstate edition of Smorgasburg has become a monthly feature from May through October. At the end of our tour, he mentions the name Richard Florida.

“Have you read any of his books?” Moss asks. He explains that Florida, beginning with the 2002 release of his book, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life, was a proponent of revitalizing depressed cities by luring artists to them. But recently he realized that approach is contributing to hyper-gentrification. (One wonders how this hadn’t occurred to Florida sooner, given what began happening in Soho in the 1980s. )Florida has since recanted, and recently published something of a mea culpa, The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can Do About It (Basic Books). But it’s too late for Florida’s suggestions for ways to “bring about a new and more inclusive urbanism that encourages innovation and wealth creation while generating good jobs, rising living standards, and a better way of life for all,” as Florida writes in the introduction to The New Urban Crisis. Moss says, “Florida has had an effect on so many cities, and once they get hypergentrified, there’s no turning back.”

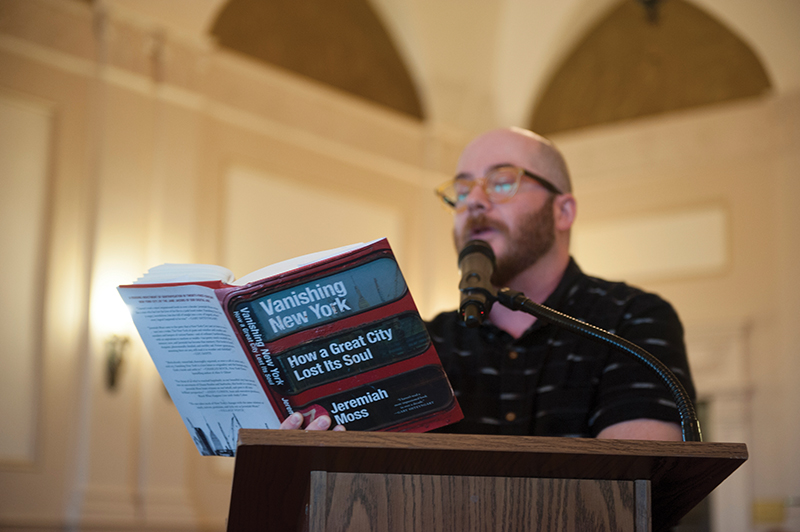

A Reading at City Hall

About 100 people show up for the book event at City Hall, filling the benches in the council chambers. I ask for a show of hands: How many people used to live in New York City? How many moved upstate because they got priced out? Most in attendance raise them high.

I interview Moss, looking for him to interpret his book and what he’s witnessed in New York City as warning signs for Kingston. It turns out that I’m not the only one wanting him to read the tea leaves.

“I hear from people all over the country, asking the same questions,” he says. “I’m hearing from people in San Francisco, Boston, Portland, Seattle. This is happening everywhere.”

But people in Kingston want to ask questions, too. After our conversation, a woman steps up to the mic. “My parents lived in Greenwich Village from 1950 to ’65,” she explains. “They were raising my sister and me on my father’s modest income, four blocks away from Washington Square Park. Can you foresee a way that a city could ever go through the kind of change New York has, and return to being a place where working-class, or lower-middle-class, or middle-class people could actually live and raise families?”

Moss responds, “I think we can go back by going forward. We are in a revolutionary place right now. It really is about more democracy. The more we fight for more democracy, for more citizenship, the more we can change the larger system—that’s where it has to be changed. “

I can’t help but ask Moss, “How do we, as artists, play a different role? What can we do to allow for growth, but stem the tidal wave of gentrification?”

Moss doesn’t have one simple answer, other than to recommend getting involved—attending meetings, especially about rezoning and planning, and fighting cities giving tax breaks to developers—to become activists for things like commercial rent control, and stand up for the poor. “But it’s hard to stop,” he admits. “There’s only so much we can do, unfortunately. I’ve tried to fight for small businesses. Fighting for one at a time doesn’t work. Fighting for scraps of affordable housing, it just doesn’t work. It raises the awareness of it, which is great, but without getting at the policies that are creating this, nothing’s going to change.”

That’s not to say that Moss is completely done with standing up for mom-and-pop stores. “I haven’t given up on staging protests or #SaveNYC,” he says. “I think it’s useful to call attention to the issues through the individual fights, for the individual businesses.”

After the event, we head to dinner. Moss laments that the building housing his psychotherapy practice in Manhattan has been sold for an exorbitant sum. He doesn’t know what he’ll do when the rent inevitably gets jacked up.

“Have you considered moving to Kingston?” I ask. He smiles, but he doesn’t respond.