Living Wright in Lake Mahopac

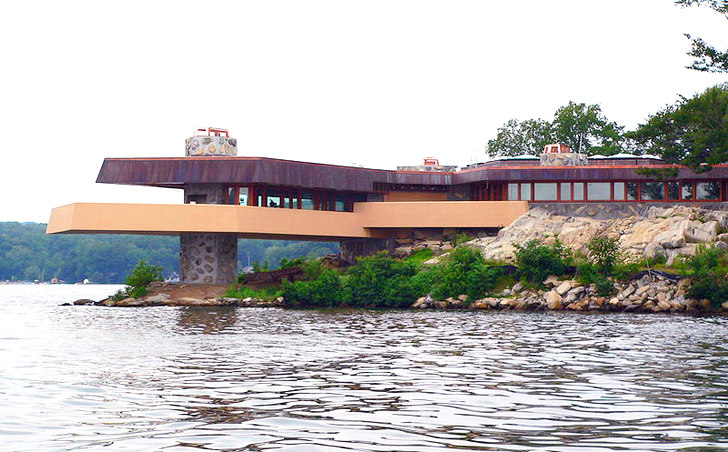

Staff | February 13, 2017 When sheet-metal mogul Joe Massaro bought Petra Island in Lake Mahopac for $700,000 in 1991, it came with an exquisite 1,200-square-foot Frank Lloyd Wright guest cottage designed in 1950. Decades later, the American Institute of Architects named Wright “the greatest American architect of all time.” The cottage was ancillary to Wright’s plans for a spectacular 5,000-square-foot master residence fabricated from structurally reinforced concrete around a giant rock outcropping, which was never built.

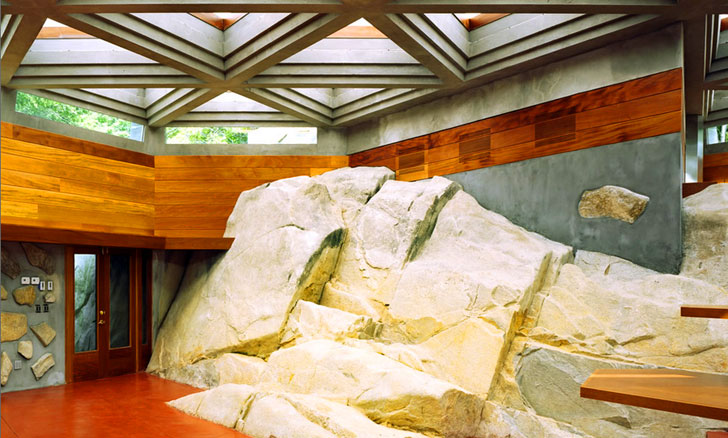

When sheet-metal mogul Joe Massaro bought Petra Island in Lake Mahopac for $700,000 in 1991, it came with an exquisite 1,200-square-foot Frank Lloyd Wright guest cottage designed in 1950. Decades later, the American Institute of Architects named Wright “the greatest American architect of all time.” The cottage was ancillary to Wright’s plans for a spectacular 5,000-square-foot master residence fabricated from structurally reinforced concrete around a giant rock outcropping, which was never built.

Well, at least not until Massaro sold his business and found himself with plenty of money, time, and a proven ability to cultivate asset value. “I have a real good batting average,” says Massaro, now the principal investor in a Boston software company he claims will revolutionize commercial construction.

In the 1950s, Lake Mahopac was a middle-class summer community, convenient to New York. At age 83, Wright, a lifelong Midwesterner, was basking in the chatter of Manhattan success, buoyed by the fame surrounding his commission for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

The rocky 11 acres of heart-shaped Petra Island inspired Wright precisely when he could most afford to be choosy. After decades of emotional and financial turbulence, Wright’s life finally seemed balanced. Many believe the prolific artist and educator was peaking creatively.

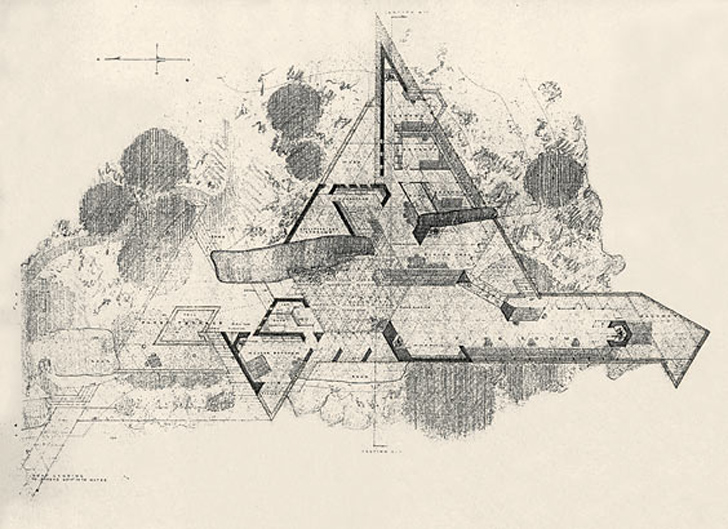

An engineer named A. K. Chahroudi commissioned Wright to design a dramatic cantilevered cliff residence envisioned to surpass Fallingwater (1935) as his crowning achievement. The guest cottage was merely the companion structure. Allegedly due to lack of funds, Chahroudi never built the great house, and eventually sold Petra Island, but copies of the drawings remained in the engineer’s family.

According to Massaro, Chahroudi’s widow confided that her husband “never intended to build the big house.” But the client challenge of creating—for an engineer!—a higher-tech masterpiece in Wright’s signature “late organic style” was the only way to court the notoriously fussy genius into drafting the stunning, smallish cottage, built in 1952.

Lovers & Loathers

“I think me and Frank, we would get along,” says Massaro, a poker enthusiast and grandfather of four who also owns a conventional home in the town of Mahopac, where his wife of 45 years, Barbara, prefers to live. They meet for lunch. The Massaros also have a condominium in Florida.

“Barbara says the spiders need saddles out there, so it’s really mostly just Joe’s,” says family friend Jim Libby.

Libby’s the executive director of Petra Production Ltd., soon to release Building Wright Today. The documentary, eight years in the making, covers every aspect of the construction and controversy surrounding Massaro’s decision to build what he considers Wright’s residential masterpiece. Actor John Amos, whose television work includes “Good Times,” “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” and a recurring role in “The West Wing,” recently completed the film’s voice over. At press time, Libby was interviewing musicians to compose the score. The golf buddies-turned-filmmakers had hoped to debut the documentary on PBS, but their marketing fee of $15,000 “is just too high,” says Massaro. Libby now plans to pitch the documentary to various cable networks and sell dvds directly to consumers.

An aggressive negotiator with a gift for making snap decisions, Massaro knew little about Wright when he bought Petra Island. Today he’s an aficionado. He collects related books and art. The colorful den mural pays homage to Wright’s Socrates Zaferiou House in Blauvelt, designed in 1956 and built in 1961. But one organization for which Massaro has no love is the venerable Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in Chicago.

Pursuant a cashless legal settlement, Massaro may only claim the big house on Petra Island is “inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright.” Consequently, Massaro House, finished in 2008, attracts both fawning lovers and fanatical loathers.

While duly faithful to Wright’s plans, the headstrong tycoon made a mere handful of alterations he describes as “field-expedient.”

Purists castigate Massaro for using curved skylights instead of flat, capping the chimneys to keep out snow and rain, but most especially, for altering the way rubble stones extrude from the home’s walls. Massaro staunchly defends all his choices. “The small bedrooms and baths, the built-in furniture—they’re all exactly as Wright designed.”

What’s not disputed is that Massaro House is the only Wright house erected in the site for which it was designed since the architect’s death in 1959. “I finally built the big house, and no matter what anyone says, this is a Frank Lloyd Wright house,” says Massaro.

Massaro says the Foundation initially demanded $450,000 for blueprints and posthumous construction-authenticity supervision. He countered with $200,000. A bitter dispute ensued. Massaro, who had run a union shop and was on its national labor relations board, finally had enough of pedantic academics telling him what to do.

He’d made his fortune making metal for duct work, and by golly, Massaro House was going to have air conditioning, which Joe installed himself. Furthermore, building permits were now more complicated than they were 60 years ago, when New York had no energy code. There have also been significant improvements in concrete technology. Massaro attends the annual concrete manufacturer’s trade show in Las Vegas to stay informed and also play a little Texas Hold’Em.

“See, nobody handed me anything,” says Massaro. “I worked 16-hour days for 15 years, so I didn’t really see my family grow up, I had no business education, and one day I was working for them and the next day they was working for me.”

Architect of Record

“Hon, there’s a man trying to get onto the island!”

One summer afternoon in the late 90s, Massaro received an urgent telephone call from his wife. “She said, hon, there’s a man trying to rent a boat from Mahopac Marina to get onto the island!,'” says Massaro. Barbara quickly nixed that. “She’s very private, very protective,” he says.

A week later, the thwarted boat renter contacted Massaro directly, identifying himself as Thomas A. Heinz, AIA, an architect from Illinois and author of many books on “Mr. Wright.” Heinz explained that he’d photographed every existing Wright house except the Chahroudi cottage. Heinz politely asked Massaro to grant him the privilege of a tour. Massaro agreed. The men became friends. When the rift with the foundation blew up, Massaro immediately hired Heinz to execute Wright’s plans and be the architect of record for its construction.

Attaching the respected Wright scholar to the project lent Massaro’s dream much credibility. They’ve remained close. Heinz visits Petra Island every summer with his wife. “Being inside Massaro House is like being on a ship that is docked, ” says Heinz. “You see water on all sides, it’s very quiet, and the air is clear and refreshing.”

And That’s The Way It Is

Joe mostly uses Massaro house as the ultimate man cave. He cleans the windows and floors and maintains the grounds himself. His family visits by invitation only. But Massaro makes the space available for several fundraisers a year, raising thousands of dollars for charitable causes. He thinks he pays the highest property tax assessment in Putnam County, without benefit of police or fire services.

“When Walter Cronkite came to see it, he walked in and said, “I feel Frank here,'” says Massaro with pride. The late anchorman knew Wright personally. Massaro keeps several photos of the “most trusted man in America” on a particularly Wrightian African mahogany bookshelf alongside family pictures. And that’s the way it is.

This article was originally posted in May 2012 on Chronogram.com.

Read On, Reader...

-

Jane Anderson | April 1, 2024 | Comment A Westtown Barn Home with Stained-Glass Accents: $799.9K

-

Jane Anderson | March 25, 2024 | Comment A c.1920 Three-Bedroom in Newburgh: $305K

-

-

Jaime Stathis | February 15, 2024 | Comment The Hudson Valley’s First Via Ferrata at Mohonk Mountain House