Rustic Gourmet: Chef Bryan Calvert keeps life simple—in and out of the kitchen.

Upstater Magazine Summer 2017 | By Susan Piperato | Roy Gumple

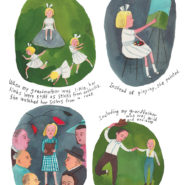

When chef Bryan Calvert opened his restaurant, James, in Prospect Park, in June 2008, Brooklyn was still finding its place on the food map. But after feeling cooped up for years while working in Manhattan restaurants, Calvert found being a Brooklyn restaurateur refreshing. James, named for Calvert’s great-grandfather, a cook who emigrated from Ireland to open a restaurant in Harlem, is small, with just 45 seats, and was designed to be the upscale version of a classic, cozy, corner restaurant. Hoping to showcase his talents, Calvert filled the menu with complex “special-occasion” dishes, and basked in his good luck.

“In Prospect Park, I had been living above a bodega, and then the neighborhood changed, and this restaurant opened downstairs for two years, called Swirl. They didn’t quite make it, so the space opened and the opportunity came up for me,” Calvert says. “Everything fell into place.”

Nonetheless, he faced naysayers. “At first people were like, ‘Why are you going to open a restaurant in Brooklyn? No one’s going to come.’ But I had the money and I was ready to do it, so I went for it,” Calvert says. “Brooklyn is really hot, for almost a decade now, and it’s national. You don’t need to be in a big city to do great food now. All these smaller cities and rural areas are doing great food. People are more savvy about good food and expect more, and it started in Brooklyn.”

But three months after James’s opening, the economy began faltering, starting with Lehman Brothers’ collapse. Suddenly, the restaurant’s customers dwindled. “People became far more conservative—they were still going out to eat, but they were concerned about cost and what’s going to happen,” Calvert recalls. “Even people who could afford fine dining and could go out and spend lots of money didn’t, in emotional response.”

So Calvert reassessed James. The restaurant’s décor was a success: The tin ceiling, long bar, chocolate-colored banquette, and white brick walls mostly unadorned except for a portrait of the dapper, mustachioed, and dark-eyed James Calvert combine to create what the New York Times called a “charmingly compressed feel.” But the menu needed revamping. “People wanted comfort food, they weren’t so adventurous, they wanted to heal themselves,” he says.

Formerly influenced mostly by French cuisine, Calvert decided to shift toward Italian culinary traditions. “In Italy, they make incredible dishes just from garlic, tomatoes and pasta,” he says. “So I basically pared down, put less ingredients on the plate. For an entrée instead of a protein and seven to eight ingredients, I used a protein and three to four ingredients. I didn’t use less-expensive ingredients, but I simplified. I learned that simplicity is actually harder to do, but you can get better results. You can showcase the ingredients more when they’re not hiding under each other.”

The new menu was a hit with both diners and critics. “Classic food has greater longevity,” Calvert says. “Most trendy food is interesting and delicious, but it’s also overly complex, too thought out, so in the end, it disappears, it’s just a trend.” Plus, the simpler dishes cost less to produce, so Calvert lowered the prices and instituted a burgers-and-all-night-happy hour on Mondays. Nine years later, James continues to thrive. Thrillist noted its “all-around fantastic brunch menu.” At New York Magazine, it was a Critics’ Pick, lauded for its “refined, hyper-localized touch,” and Brooklyn Magazine chose it as one of “7 Restaurants Where You Should Always Order Dessert,” principally for its cheesecake, which James sells through its retail division, Cecil & Merl (also named after beloved relatives). Huffington Post included James on its “New York’s Best Sunday Night Suppers” list, calling it “a treasure” that’s “culinarily forward thinking and—sadly, an almost necessary disclaimer for BK restaurants these days—not pretentious.” And the New York Times praised the “small, sweet” restaurant for its “succinct, appealing menu,” describing James as “the kind of modest, warm refuge produced by a chef who wants to simplify things, to personalize things, to work on a scale that doesn’t require or invite the meddling of too many outsiders.”

James’s dishes included herbs grown in a tiny adjacent outdoor garden. But as the restaurant’s popularity grew, Calvert established a large garden at his weekend house in Kent, Connecticut, to grow more ingredients. “That was dear to my heart,” he says.

But commuting between Kent and New York—not just between the restaurant and his upstairs apartment—made Calvert reevaluate his life. “First I was going up [to Kent] on weekends, and then during weekdays, and I really liked the lifestyle,” he says. Besides, he confesses, he “had no intention of staying in New York for more than a few years, just to get some experience, but then life happens, and 10 years go by. I realized I would probably be happier and more fulfilled living outside the city as much as possible.”

Though Calvert was born in New York, his family moved to suburban New Jersey when he was in elementary school. “It was in the ’70s, the whole ‘Bronx-is-burning’ scenario,” he says. As a middle school student in Westfield, he got a job washing dishes at a local restaurant, then moved on to food prepping, assisting a baker, and “just never stopped,” he says. After high school, he worked as a cook before heading upstate to the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, where he earned an associate’s degree in 1990. He completed a bachelor’s degree at Boston University’s School of Hospitality and Administration, working as a teaching assistant in the kitchen classroom. “I met Julia Child and Jacques Pepin and all these really well-known chefs who taught there—really great exposure to a lot of really cool people going through the doors there,” he says.

Working as a journeyman chef and traveling in stints for several years took Calvert to many rural locations in Europe, California, Fire Island, and along the Appalachian Trail before he landed in New York. There, he worked as a sous chef for his former BU classmate, Rocco Dispirito, who founded Union Pacific. “The focus was much different than it is today,” Calvert recalls. “We bought stuff from farms, and I was at the farmers’ markets all the time, but it was mostly about getting the most exotic ingredients from all over the world.”

But after five years of 90-to-100-hour work weeks, Calvert needed a break. So when his stylist girlfriend mentioned that famed photographer Annie Liebowitz and her partner, the writer Susan Sontag, who died in 2004, were looking for a personal chef, Calvert jumped at the chance, cooking French-influenced food for the couple upstate at their Rhinebeck mansion and returning to New York to cater Liebowitz’s photo shoots.

“I didn’t realize that when you work for someone as prominent as Annie, all of a sudden a lot of people start following you,” he says. He founded Bryan Calvert Catering, cooking for New York’s big-name photographers, working out of Blue Hill chef Dan Barber’s downtown kitchen until finding his own space in Long Island City. Then Calvert joined forces with his then-wife, events organizer Deborah Williams, to form Williams & Calvert Events. “We did that for about 10 years,” he says. “That was a blast, but I still considered myself a restaurant chef, so I was always looking for a space. Then James happened.”

James’s sensibility inspired Calvert’s first cookbook, Brooklyn Rustic: Simple Food for Sophisticated Palates, published in 2016 by Little, Brown & Company. The book, geared toward the home cook, combines rural comfort with urban worldliness. One reviewer praised the book’s recipes for their “finessed familiarity.”

To formulate Brooklyn Rustic, Calvert asked friends, family, and colleagues what kind of cookbook they wanted. “They all said, ‘I want recipes for a dinner party for four to six people, serving under six courses, and to be able to cook it all in one to two hours,’” he recalls. The result, he says, is “a collection of recipes for the home cook that I’ve used over the years, both professionally and personally. They’re accessible and encourage using good, local ingredients.” But the book is also the result of his own evolution as a chef. “When you’re younger, you want to wow people. But as you get older, you never want to stop learning things, but you realize that simplicity is a better approach,” he says. “I’ve wanted to do my own thing, not take myself too seriously, cook from my heart, and just have fun.”

Brooklyn Rustic’s dishes include some James favorites: Cured Salmon; Black Kale Salad; Roasted Asparagus with Sea Salt; Lemon and Blueberry Tart; and Dulce de Leche Cheesecake; along with cocktails by James’s “go-to cocktail guru” Justin Lane Brigs, like the Window Box Collins and its featured Parsley Syrup. Spread among the recipes are short yet charming essays providing “little tips that can make a big difference” from Calvert on every aspect of cooking, from “Set Up for Success” to “Perfect Ripeness,” “How to Select Olive Oil,” and “Preserving Herbs.”

Inevitably, Calvert decided to simplify his lifestyle to match his cooking style. In 2015, he gave up his Kent house and bought a cabin and 25 acres outside the village of Andes, in Delaware County, New York, a three-hour drive from Brooklyn and a 15-minute drive from the town of Delhi, home to dairy farms. Finding Calvert’s place can be tricky. The area lacks GPS and cell phone service, requiring visitors to follow a stream bed and look for a neighbor’s sign proclaiming “Rabbits for sale” to know where to turn for Calvert’s long, uphill driveway.

His cabin sits at the top of a hill, as charming as a reader of his cookbook would expect. Wrapped with a porch and deck, it overlooks a wide green lawn surrounded by forest. There are flower beds, a sizable vegetable garden, abundant blueberry bushes, Calvert’s pickup, and wide sweeps of both sun and shade.

Inside, things get more urban. Calvert renovated the place himself, including building a staircase out of reclaimed wood, and made his own kitchen workbench extra high to fit his tall height. In the living area are a woodstove and two British vintage-inspired leather chairs from designer Timothy Oulton. There are tiny jars of pickled ramps foraged by Calvert, and, hung alongside the art throughout the open space, is a growing collection vintage serving dishes and kitchen implements that he began for the photographs in Brooklyn Rustic. “Food tells a story, and so if the stuff we put it on has a story, that makes it more interesting to me—that’s why we relish old things like our great-grandmother’s china, we have a symbiotic connection to it,” he says. “Buying kitchen stuff blindly is not as rewarding—just like buying food blindly.” And although collecting used kitchenware is also more economical, admits Calvert, “It’s not so much about cost as it is about the journey. Scavenging old junk shops takes time.”

These days, Calvert spends a few days each week in Brooklyn working at James. The rest of the time, he’s exploring nearby parklands and villages or relaxing on top of his hill, “in exploration mode,” figuring out his next move, doing lots of cooking, and watching his dogs—Georgia and Fisher—enthusiastically patrol the property for deer and bears. Although Calvert admits it took him a while to get used to the cabin’s quiet, he now “can get pretty Zen about things up here,” he says. “In this busy world, it’s a gift just to wash dishes.”