Talk of the Town: Newburgh Rising

Upstater | October 2, 2013We’re assuming the New Yorker is not going to print our Talk of the Town about the Newburgh architectural tour, so we’re publishing it here, which is so close to the New Yorker that people often get them confused.

It was world peace day on September 21, and the city of Newburgh, N.Y. celebrated by erecting a peace pole in a park at the end of the main drag of Broadway. After the ceremony — the peace pole was dedicated to the late founder of World Peace Day, John McConnell, and the peace activist and the late wife of Pete Seeger, Toshi Seeger — a caravan of Newburghers took the streets to declare that peace would come to this dense city of less than 30,000. They held white balloons, waved bibles and shouted through a loud speaker: “Newburgh will rise up again. All things rise from the ashes. Don’t speak an ill word about Newburgh.”

Ill words are sometimes the only ones spoken about Newburgh these days. The city is known, at least in the press, as the murder capital of New York State (technically, Rochester takes that title, but Newburgh is a close second). Some 700 buildings within its 3.8 square miles are vacant. Gangs, drugs, blight—it is all there (the blight is common; the gangs and drugs are limited to a few notorious streets).

But there is so much good to say, mostly about the community of extremely passionate Newburgh activists, who are working incredibly hard to save the city. Also: mansions with Hudson River views going for peanuts, and renovated Italianate townhouses that a regular old middle class person can afford. Warehouses are occupied by artists and artisans who pay practically squat to do their work along the Hudson. It’s a beautiful spot, and filled with potential.

So later that same morning, 25 New Yorkers boarded a bus for an architectural tour of the city — to view its potential, and its high points — guided by the city historian Mary McTamaney. She was introduced to the group by Mayor Mary Kennedy. “Mary knows all of the good of Newburgh,” she said, and then cupped her mouth as if to whisper. “And the bad, too.”

“People always ask me for the naughty Newburgh tour,” McTamaney said. “This isn’t that.”

Rather, this was a tour organized by a local group called Newburgh For Newcomers, designed to lure a new crop of settlers to the city with its biggest draw—architecture. (Turns out the group is also made of realtors trying to sell some of that really beautiful and pretty darn cheap architecture, and maybe some other neighborhood groups aren’t so pleased with them—see above: passion for Newburgh.) Their slogan: Like Brooklyn, but affordable.

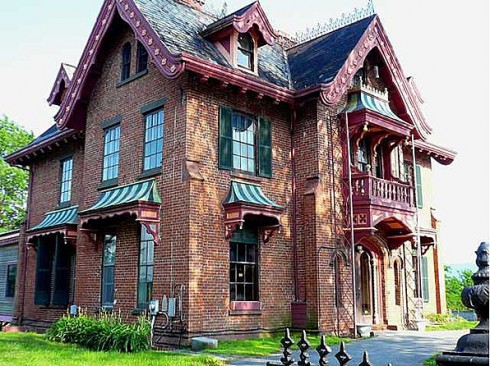

The bus gamboled past a crumbling and abandoned Richardsonian Romanesque mansion (city-owned, on the market for $124,000), a renovated three-bedroom early 19th century house ($212,000) and a Gothic Revival stunner with Hudson River views designed by Calvert Vaux, which recently sold for less than $350,000. There were audible oohs and ahhs, and a couple of gasps. “That house is beyond gorgeous,” said one prospector from Long Island. Moments later, the bus passed at dilapidated second empire Victorian and a few riders tsk-tsked in shame.

The architecture, no matter its state of decay, is stunning—or at least, potentially stunning. The list of architects and designers who created housing here is impressive: Andrew Jackson Downing, Calvert Vaux, Frederick Clarke Withers, to begin. “Here’s a mansion that we believe was designed by Stanford White so that his mistress, Evelyn Nesbit, could have a Hudson Valley getaway,” McTamaney said, nodding toward a white house in mild disrepair. “We’ve never been able to prove it, but it’s his style.” Before it was the epicenter of 19th century architecture Newburgh was the site of George Washington’s Revolutionary War headquarters and the place where Thomas Edison wired a house in 1883. In other words: Newburgh was once a showpiece. Now, it’s a cautionary tale.

Occasionally the bus would stop to welcome Newburgh-boosting visitors from various non-profits. On the corner of Grand Street and 1st street, the 28-year-old director of the Newburgh Historical Society boarded the bus with an armload of pamphlets. “The most common question people ask us is ‘What happened to Newburgh? Why is it like this?’” said Johanna Porr. “In October, we’re having an event to answer the question.”

She went on to summarize: urban renewal—which took out a third of the city’s historic district; deindustrialization; white flight (the city is 42% Hispanic and 25% black); a lack of tax-paying businesses that increased city taxes (taxes on that abandoned mansion: $18,000 a year) and a plague of absentee landlords. They often refer to Newburgh’s ills as the perfect storm.

Still, Newburgh’s boosters prefer to focus on the positive. It has a wealth of new businesses, artists and artisans who moved up from the city to take advantage of its wealth of industrial, or maybe post-industrial, space. It has home restorers fixing houses on scary blocks so as to bring a little hope amid the dilapidation. As the bus passed houses with broken windowpanes and stoops that seemed duct taped on, McTamaney said, “This is a landlord neighborhood, but there are some real bargains.” When it wheeled by the former mayor’s house, she said, “The mayor sadly died of a heart attack while she was out on the lawn watching the fireworks….So that house should be coming up for sale soon.”

The bus passed the site where grand mansions were torn down during urban renewal for low rise public housing. “Large estates were taken down to accommodate more intense housing,” she said. A rider asked about a Dutch Revival church in the center of what was the old town square, that seemed on the verge of collapse. “It’s been abandoned since 1967,” she said. “That’s what Mother Nature does to a building that’s not embraced.”

After cruising through a rough neighborhood where tens of neo-folk-Victorian homes had been neatly erected by Habitat for Humanity, the bus came across an 18th century structure with the roof sloughing off. “People never want to take that one down because of its history, but it’s rotted,” said McTamaney. Her good spirits dissipated for a moment. “This is the worst spot in the city,” she admitted.

One passenger from Brooklyn, already won over by the city and aching for its people and its potential, suggested that all the city needed was a billionaire patron — Bloomberg comes to mind — who could donate the money to rescue these properties. Or maybe Pete Seeger could add the city to his list of environmental causes. Some famous person could adopt this city.

So far no billionaires have felt what the passenger from Brooklyn felt: an immediate and deep-seeded love for the place. A fellow Brooklynite, Brad Crownover, who had purchased a property in Newburgh, said it was indeed like New York City. “You either fall in love with it immediately,” he said, “or you start making plans to leave.”

Read On, Reader...

-

Jaime Stathis | February 15, 2024 | Comment The Hudson Valley’s First Via Ferrata at Mohonk Mountain House

-

Ryan Keegan | November 28, 2023 | Comment Hunter, NY: Full Circle

-

Ryan Keegan | October 17, 2023 | Comment Ellenville’s Next Chapter

-

Joan Vos MacDonald | September 28, 2023 | Comment The Reinvisioned Livingston Manor Fly Fishing Club