What We Learn from Public Gardens

Michelle Sutton | July 1, 2015

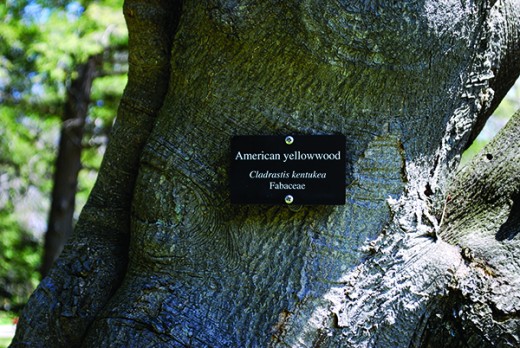

Classic plant display label. – LARRY DECKER

Editor’s Note: This article has been reposted from Chronogram.com with the author’s permission.]

Horticultural Utopias

Public gardens include arboreta (plural of arboretum) and botanical gardens. Historically, arboreta have focused on curated collections of woody plants (trees and shrubs), while botanical gardens have had a broader focus, featuring showy gardens and/or collections of both woody plants and herbaceous (non-woody) plants. Many public gardens began as private gardens by people who were passionate plant collectors.

Increasingly, college campuses are declaring themselves to be and/or formally registering as arboreta, maintaining their trees as collections with plant labels, databases, educational programs, and master plans. Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson is an exciting example of this; the entire 550-acre Bard College campus was dedicated as an arboretum in 2007.

The most exciting aspect of my own horticulture education was any time I came in contact with public gardens. I worked and studied in the Virginia Tech Hahn Horticulture Garden, interned at the Holden Arboretum in Ohio, and went on field trips to see dozens of public gardens. I got to live my dream job when I worked in the education department of Cornell Plantations, the arboretum, botanical garden, and natural areas of Cornell University in Ithaca. The magic of being able to walk around world-class gardens whenever I stepped outside my office never faded.

I love the public gardens with big budgets; they can do outrageous displays and ambitious research. I also love those smaller ones that are underfunded or in decline. I often find them to be the most inspiring, because they are permeated with the love of those tireless volunteers who are keeping them going. In either case, be they world-class or regional and scrappy, there is so much one can learn from public gardens. They are a key part of my ongoing education in horticulture.

The Conservatory Garden within Central Park. – LARRY DECKER

Happy Immersion

One of the best ways to learn plants is to visit a public garden in your region at regular intervals throughout the growing season. Or even better, you can volunteer to work in a specific garden or in the greenhouse. Orange County Arboretum in Hamptonburgh has more than 50 active greenhouse volunteers. They are trained by horticulturist Pete Patel, who says, “Learning plants is a business of repetition: working with them, seeing how they grow and react to different circumstances, and seeing the tags over and over with the Latin and common names.”

In addition to offering a popular volunteer program, the Arboretum hosts educational programs for school groups—more than 1,300 kids a year—on composting, good bugs / bad bugs, aquatic studies, bee hives, and how to plant a plant. Patel says, “The dedicated volunteer instructors really excel at these children’s programs.” In turn, volunteers get an education—informally, by working in the gardens and with the public, but also by taking adult education classes for free, in things like pruning, deer-resistant planting, and horticultural arts. A public garden can be a place to bring your skills and passions and have the freedom to create something really neat.

To continue his own education, Patel visits public gardens and takes classes and trainings at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx. “The staff instructors there are people at the top of their field and have access to tremendous resources,” he says. “I enjoy the plant collections, but I learn the most from direct contact with those professionals who take us behind the scenes.”

Patel’s favorite botanical garden is the 28-acre Wave Hill, also in the Bronx. It’s similar in size to the Orange County Arboretum (35 acres). Patel resonates with the mission of Wave Hill (especially, “to explore human connections to the natural world through programs in horticulture, education and the arts”). He hopes to cultivate, over time, the Wave Hill qualities of beauty, intimacy, and horticultural playfulness at the Arboretum.

Plant Relationships

At public gardens you can observe how plants are used in relation to one another for best ornamental effect, see how plants are sited based on their cultural needs (e.g., which ones are suited for lowland wet spots), and be introduced to new plants. Arboreta and botanical gardens are the ideal places to learn plant identification; they frequently arrange their collections to help you in your plant-ID studies.

For instance, at the Orange County Arboretum, you can see a dawn redwood tree growing alongside a bald cypress tree so you can study the subtle differences between the two oft-confused species. You’ll note, for example, that the dawn redwoods have “armpits”—i.e., where the branch meets the trunk, there is a telltale hollow beneath that juncture. (By contrast, bald cypress branches swell slightly where branch meets trunk.)

Public gardens often feature collections of the same genus—oaks, maples, rhododendrons, etc.— that make it easier for students of horticulture (formal or otherwise) to compare and contrast the many different species or varieties. Other collections will have an educational theme, such as the urban tree collection at Cornell’s arboretum that displays the toughest trees for urban use in that region.

Recently I took my mother to see Stone Crop Gardens in Cold Spring, which describes itself as a “Plant Enthusiast’s Garden.” Along with a terrific garden map, they graciously provided us a “bloom list” that corresponded to numbered stakes in the various containers and flower beds. Most public gardens are not able to keep all their plants labeled at all times; it’s a labor-intensive proposition and even the sturdiest of labels have a way of breaking and disappearing. The “bloom list” approach with numbered stakes at Stone Crop is a great compromise (although they do have permanent labels on many plants as well).

When you do see plant labels, you may be seeing a display label or an accession tag. A display label usually has the bare bones of ID information: binomial Latin name, common name, and perhaps plant family. An accession tag has more information, often including the nursery from which the plant came, the geographic origin of the species, and an accession number. For instance, the accession number 2001-185A would tell you that this was the 185th plant accepted into the collection in 2001, and the A indicates that it is part of a group of others of the same species, labeled B, C, etc. (If there is no letter, that means there was only one of its species acquired at that time.)

Stone Crop excels at many things, including serious plant collecting and sophisticated design. It’s stunningly beautiful at every turn. One of their gardens I find delightfully plant-geeky: the Systematic Order Beds. Each bed features a plant order and representatives of plant families within that order. For instance, there’s a pea order (Fabales) bed that contains plants from the four families (Fabaceae, etc.) within the order. When I was there, beautiful false indigo plants (members of the Fabaceae family) were in bloom in white and purple spikes in that bed. For someone interested in botany, botanical nomenclature, and/or plant taxonomy, this garden will be of special interest.

Public gardens show us ways of putting plants together for best ornamental effect. – LARRY DECKER

Lastly, public gardens present us with ideas for new ways of using plants. When I worked at the botanical garden at Cornell, my office overlooked the groundcover collection. Many visitors had thought of groundcovers in a very limited way—the ivy, the pachysandra, the periwinkle. This garden showed how many different kinds of plants, including hostas, ferns, and lady’s mantle, could be used as groundcovers. Weeds could rarely find purchase among all that lush foliage. Elsewhere in the botanical garden, talented staff integrated edible plants like herbs, dark purple kale, and brightly colored Swiss chard into the flower borders to great effect, giving visitors ideas to take home.

Read On, Reader...

-

Jane Anderson | April 1, 2024 | Comment A Westtown Barn Home with Stained-Glass Accents: $799.9K

-

Jane Anderson | March 25, 2024 | Comment A c.1920 Three-Bedroom in Newburgh: $305K

-

-

Jane Anderson | January 30, 2024 | Comment A Renovated Three-Story Beauty in Poughkeepsie: $695K