An Edible Landscape

Ana Gioia | June 21, 2015

Editor’s note: This piece first appeared on the Kingston Land Trust’s blog and is republished here with permission.

Spend just two hours observing the plant systems that surround us — experience in-depth plant identification, smell, touch, imagine, taste — and you will begin to see the entire world in a new way. You may notice a “basal rosette” interrupting a ruddy lawn, begin connecting scent with edibility and feel significantly more attuned to and part of the natural environment. Such connection to one’s natural environment is often taken for granted, but in the same way that a painter working on a house, sanding and touching up trim, begins to notice the detail and imperfections in other structures, a forager begins to see the patterns and variations of flora in their environment.

Part of it is learning the facts, like how black raspberries “tiproot,” meaning the canes or stalks bend down to re-root in the earth, thereby creating a new incarnation of the plant. And that the cane lives for only two years, the first to establish itself as an adolescent and the second to create fruit before dying back in the third year, making way for the newly matured canes to fruit and continue the cycle.

The other part is just actually spending one-on-one time with your materials — in this case, vegetation. This means observation over time, touch, attuning oneself to the subtle differences in species that make one edible and one toxic, knowing when in the plant’s life cycle it should be harvested or how different stages and plant parts can yield different tastes and types of food. Only through time does one recognize patterns within a species, a similar leaf shape for example, can inform us that Ox Eye Daisy (found in most yards this time of year) is related to the common Chrysanthemum and what medicinal use could come of that. Leaf structure, flower shape, seeding ritual — it all plays a role in plant identification and use and because the nature of life in general is impermanent and subject to irregularities, mutation and adaptation; it is a never-ending puzzle.

Thus, foraging becomes a symbol of life in general, and a fertile one at that, for it actually results in food and nourishment and connects the individual to ancient human knowledge that has been almost bred out of existence. But it is there, and there are people who have inherited that knowledge and wisdom and can share it with others.

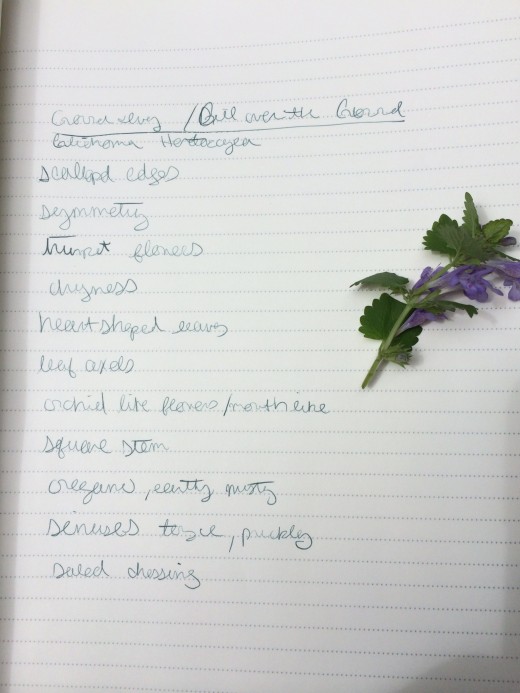

On a recent walk with local foraging guru and author Dina Falconi, I joined several other women (with some babies in tow) for a two-hour outdoor wild edibles course in Accord. Dina has been studying the local flora of the Hudson Valley for 30 years and her expertise and style of educating is unparalleled. She urged us to get close to the plants and engage all of our senses when taking notes. She also warned against jumping to conclusions when identifying something and suggested observing a plant’s life cycle and growing patterns over several months, returning to certain locations over time when necessary to confirm edibility before harvesting. Some areas should be avoided altogether, for example along major roads and the foundations of buildings.

We can learn a lot from foraging — patience, sensitivity, resourcefulness, to name a few. The most astonishing aspect of eating wild plants is how over time you can begin to link certain plants, especially the native ones, to seasonal medicinal use. Just as local honey can cure local allergies, certain plants offer particular health benefits especially at the time at which they come into season.

For more information, visit Dina Falconi’s website, where you can email her with questions, view information from her amazingly illustrated book, find recipes featuring local wild edibles and request to schedule a class or walk. When it comes to something like foraging, it is really helpful to learn about what is growing and going on in the Hudson Valley (in our own backyards!) from someone who lives here. Right now, for example, we could be preparing to harvest the abundant wild grape leaves that grow and climb all over the area and are just reaching their tender peak.

Join us Wednesday, July 29th, 2015 for an evening at Kingston Wine Co. with Dina Falconi and the Kingston Land Trust! Copies of Dina’s book, Foraging and Feasting, will be available along with samples of some wildly-infused cocktails. Come with your foraging questions!

Read On, Reader...

-

Jane Anderson | April 1, 2024 | Comment A Westtown Barn Home with Stained-Glass Accents: $799.9K

-

Jane Anderson | March 25, 2024 | Comment A c.1920 Three-Bedroom in Newburgh: $305K

-

-

Jaime Stathis | February 15, 2024 | Comment The Hudson Valley’s First Via Ferrata at Mohonk Mountain House