How D’Ya Like Them Apples

Upstater Magazine Fall 2016 | By Erik Ofgang | Photos by Eva Deitch

We were brought together by a love of cider.

On a summer’s evening in late June, seven of us gathered on the grounds of the Angry Orchard Innovation Cider House in Walden: two food and beverage writers (myself and Peter Barrett, author of the forthcoming Project 258: Making Dinner at Fish & Game, scheduled for a February 2017 release) one brewer (Christopher Basso, cofounder and brewmaster of Newburgh Brewing Co.), two Hudson Valley cider makers (Ryan Burk, head cider maker at Angry Orchard, and Leif Sundström, a longtime wine industry veteran who launched Sundström Cider in 2015), and two restaurant owners (Chris Kavanagh, co-owner of The Hop in Beacon, and Tim Reinke, owner of Birdsall House in Beacon and co-owner of Gleason’s in Beacon and Blind Tiger Ale House in Greenwich Village).

Angry Orchard is located on a 60-acre farm that has been an apple orchard for about 100 years and a farm since the 1700s. Today, the orchard’s apple trees are framed against the backdrop of the Shawangunk Ridge and the facility serves as the cider world’s answer to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. On the drive in you’ll pass an expensive treehouse, inspired by the label art on the brand’s bottles and there are also several acres where rare varieties of apples, designed for cider making, not eating, have been planted. The taproom overlooks the orchard and there are outdoor tables and a fire pit.

Together, our group of seven tasted more than a dozen ciders from nine New York cider makers who hailed from throughout the Hudson Valley, including Brooklyn Cider House from New York City. We also enjoyed abundant pairings supplied by Bistro-to-Go in Kingston.

We drink just feet away from Angry Orchard’s actual orchard. The sky was slightly overcast and as the evening wore on a storm rolled in, giving the orchard an appearance that more than lived up to the “angry” portion of its name. For several hours we engaged in a lively and passionate discussion about both the ciders we sampled and cider’s place in New York, liquor stores and the universe at large. Though none of us knew one another well at the start, by the end of the tasting we were trading jokes and sharing rare bottles.

What follows are some of the highlights of our great cider tasting.

Big Apple State

New York is the second-largest producer of apples in the country, trailing only Washington State. The Hudson Valley is known as the “apple belt” for its high concentration of apple growers. A growing number of cider makers in New York City and beyond are taking advantage of this crop by making innovative ciders. At the same time, there is a growing appreciation for cider culturally; this is evident in New York City at Wassail, a Lower East Side bar and restaurant passionately dedicated to cider that opened in 2015, and in events like Hudson Valley Cider Week, a multiday festival that takes place each summer at dozens of locations in the Hudson Valley.

“Cider has reentered American culture in recent years, reviving old traditions while sparking new discoveries,” says Sara Grady, vice president of programs at Glynwood, an organization that promotes food and farms in the Hudson Valley. “I believe it is part of the evolution in our relationship to food and drink—cider is a beverage that can connect us directly to land, nature, farms.”

Grady, who also helped create the New York Cider Association, adds, “The Hudson Valley is a historic apple region, therefore cider can be our signature drink. Orchards define our landscapes, and so should cider be at the center of our cuisine. Although cider may be a less familiar beverage at our tables, apples have grown well here for a very long time, so cider is in fact a most appropriate and defining beverage for the Hudson Valley.”

The region’s long-established apple culture and burgeoning cider culture are part of the reason that Angry Orchard, owned by the Boston Beer Company, which makes Samuel Adams, chose New York for the site of its physical orchard. In the fall of 2015, the national brand opened its research and development center in Walden. The facility, which is open to the public, specializes in small- and test-batch ciders with an emphasis on barrel aging and wild fermentation. These ciders also showcase the unique flavors and characteristics of New York apples, since, like wine, the best ciders draw their distinct flavors from the terroir of the region in which they are grown.

Grady says that the unique characteristics Hudson Valley apples provide cider are still being discovered. “Many of the craft cider makers who are also apple growers are seeking to create ciders with a sense of place — to produce cider that is an expression of the fruit, the trees, and the land. These ciders tend not to be manipulated by method or altered by flavorings, and in style they often tend to be dry, perhaps even still or naturally sparkling, more refined, even austere.”

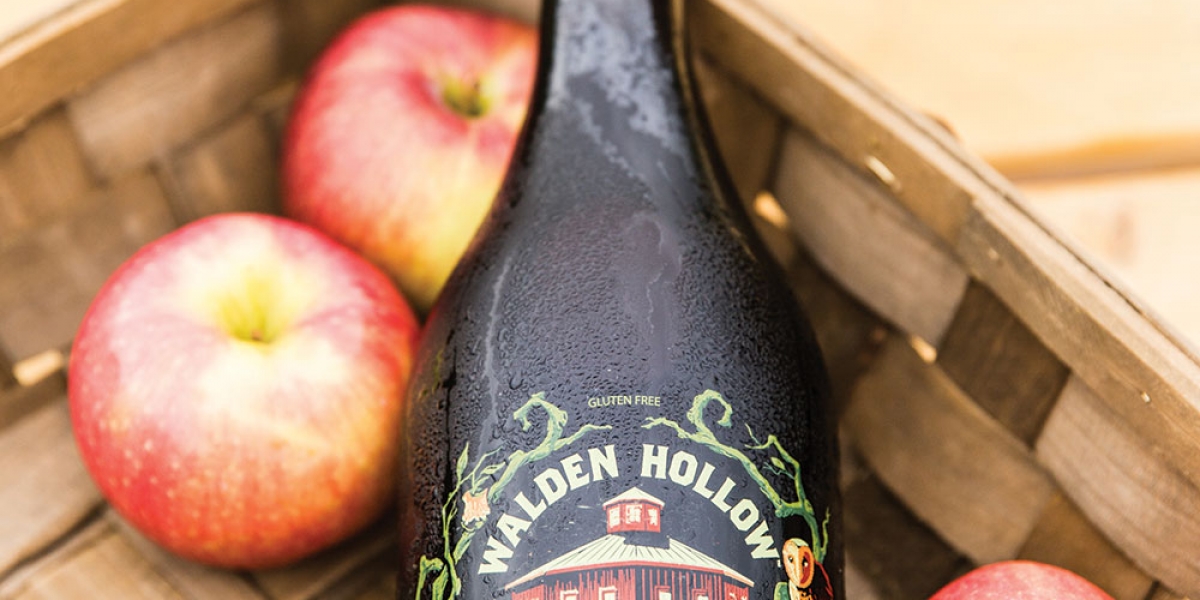

We sampled a perfect example of this with Angry Orchard’s Walden Hollow. The limited-release cider was made with apples from the company’s orchard and other New York apples. Designed to be a “snapshot of a place and time,” according to its label, it’s a tasty one. Dry and light with subtle, bright flavors, it won over all of the panelists. “This is the kind of thing where you’re naturally going to drink it again,” remarked writer Barrett, as he reached for a second sample. Basso, from Newburgh Brewing Company, enthusiastically proclaimed, “This is how you get beer drinkers.”

Draft Dodging

As we sampled solid ciders, including Brooklyn Cider House’s Still Bone Dry and some of Orchard Hill’s small-batch ciders, we talked about cider’s place alongside beverages like wine and beer.

Barrett remarked that although most people think of cider as more like beer, it is far closer to wine. “That’s part of the conundrum,” Angry Orchard’s Burk responded. “What are we to most people?”

Cider was once one of the United States’ most popular drinks, but prohibition, matched with changing drinking habits, led to a long decline for the industry, from which it has only recently begun to rebound. As as a result, most people are still learning how to drink cider.

At Newburgh Brewing Company, noted Basso, one guest tap is devoted to cider, but those who order it often don’t pay attention to which brand they’re getting. “Nobody orders it by name,” he said. Instead, “They say, ‘I want the cider.’”

Kavanagh, from The Hop, said he would like to carry more ciders at his establishment, but lamented the fact that many high-end ciders are not available on tap. In order to get beer enthusiasts at places like his to cross over to the cider world, he added, they need to be able to try a high-quality product by the glass.

Sugar, Spice, but maybe Not So Nice

A variety of hopped and otherwise flavored ciders were submitted for the tasting. In the past, I’ve enjoyed some hopped ciders and flavored cider concoctions, but I have to admit that, compared with some of the more traditional-style ciders we tried, these flavored ciders didn’t quite measure up.

Yankee Folly Cider tasted too sweet next to some of the earlier ciders. Awestruck’s Lavender Hop Cider’s combination of intense flavors seemed to overpower the apple flavor. Hopped ciders from Naked Flock and Nine Pin received mixed reviews. “I think a hopped cider should be a cider first and a hopped cider second,” said Burk, who makes a hopped cider at Angry Orchard. But he praised Nine Pin in general. “I’m a big fan of Nine Pin cider. I think it’s clean, and it’s repeatable,” he said. I agree, and feel that Nine Pin’s signature cider is a good everyday cider and strong alternative to macro cider company offerings.

In addition to the ciders sampled that evening, I tried several ciders from Joe Daddy’s Hard Cider, produced by Brookview Station Winery in Castleton. Even though it was flavored, my favorite was Joe Daddy’s cranberry cider. Its tart cranberry flavor paired well with its acidic apple flavors.

Sundström was the strongest critic of flavorings in cider, suggesting that these types of beverages should not be allowed to be classified as cider, the same way there are strict definitions of what constitutes spirits like bourbon and scotch.

Apples of Our Eyes

Our tasting concluded with a sampling of Orchard Hill’s Ten66, a brandy that’s distilled and aged in French oak wine barrels, and then blended with fresh, nonalcoholic sweet cider and returned to the barrel for extra aging. This drink, we all agreed, was a tasty spirit and a fitting cap to the evening.

Previously, we had tried two ciders from Sundström Cider. My favorite was the Sponti cider, a smooth and slightly tart cider that earned praise from all present and left me craving more. Barrett said that although this high-end cider would not be out of place at a restaurant specializing in fine dining, it would also work equally well paired with barbecue food. “This is totally a red meat cider,” he said.

Sundström shared with us that he prefers not to offer his cider in smaller 375 ml bottles because he wants the experience of drinking it to be a communal one. “I want you to share this with somebody,” he said. “I want you to share the experience.”

And after sharing cider, stories, thoughts, and theories with my fellow panelists, the concept of cider as a communal beverage is one that I can certainly drink to.

Cheers!