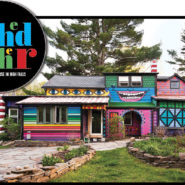

Joel Griffith – Artist/Mayor

Upstater Magazine Fall 2016 | By Susan Piperato | Photo by Roy Gumpel

Lives in: Tivoli

Hometown: Tivoli

Lived In: France, the Midwest, Brazil

Returned to the Hudson Valley from: Brazil

Joel Griffith lives by embracing contradictions. On the one hand, he’s a native son, having grown up in the tiny village of Tivoli (population 1,118, according to the 2010 U.S. Census) in northern Dutchess County, where he still lives. On the other hand, he’s a worldly guy who traveled to 33 countries on five continents and lived in Iowa (to attend Cornell College), France, and Brazil before resettling in his hometown.

Griffith is an accomplished painter, renowned for his moody, intricate, hyper-realistic depictions of upstate life, paintings that often reveal unexpected, haunting beauty in the ordinary and even the ugly. He earned his MFA in painting at nearby Bard College after growing up as a “faculty brat” with a Bard professor for his father. But he’s also Tivoli’s mayor, a no-nonsense leader who’s all too aware of the benefits (cultural, economic, demographic) and pitfalls (partying students) of having a world-class learning institution three miles away.

“I was always sort of a booster for Tivoli,” Griffith says. In the 1980s, when he was growing up there, he was part of a “skateboarding posse” out to prove their village was “cooler” than nearby Township of Red Hook, of which Tivoli is a part. “Like a lot of New York State, it was kind of rundown then,” he recalls. “Tivoli was always just a little put down, and when we were kids we sort of just got tough about it.”

Although Griffith had never previously aspired to politics, it didn’t take long for him to decide to run for mayor. “I want to protect Tivoli,” he explains. “We’ve had a handful of nice people who have moved up from the city, and they’ve got a kid or two, and they love Tivoli. They’re like, this is what I’ve been looking for. Your kid can literally ride their bike to the park and the general store, get a candy bar.”

As a village trustee for five years, Griffith focused on the problems caused by drunken college students congregating in Tivoli late at night. Gradually, thanks to his persistence, the problem was resolved. “A residential village of 1,100 people cannot absorb the partying needs of 500 undergrads—we’re just not designed for that,” he says. “So I studied college towns around the country.… They almost all have some version of the same law.” Putting through a nuisance gathering law was his first act as mayor. “Essentially, it says if you have a gathering, fine,” he explains. “But if you have a loud, obnoxious gathering, there are 13 triggers—[including] illegal parking, lewdness, noise, underage drinking, drugs, trespassing, damage to property, etc., you know, like an Animal House party—and if you have one of those parties in Tivoli, you’re going to get two tickets at a minimum of about 400 bucks.”

Initially, the law was “hugely controversial,” he admits, “but I knew there was no argument against protecting quality of life for all people in the village.” Ultimately, he says, his own experience saw him through the “contentious” situation. “I identify as a Bardian-Tivolian—I play for both teams,” he says. “I felt like a kid whose parents were fighting. You love them both and you want them to get along. I was like, ‘I can do this because I’ve watched the whole thing. I know I can get this done.’ And it’s changed quickly. There will always be a little back and forth, but it’s livable, and the village, for the first time in years, is feeling good.”

These days, Griffith is busy figuring out how to overhaul Tivoli’s 77-year-old infrastructure (“It was state-of-the-art in 1938; it’s not anymore”), recreate its identity (“If Tivoli’s not going to be a college town, we have to be something—what I would like us to be is a fabulous family village with arts and culture”), and carving out time to paint. He’s had significant success so far with the latter goal: Through November 25, six of his nightscapes will be showing at Flatiron Restaurant, located at 7488 South Broadway in Red Hook.

“It’s really hard to serve two masters,” he admits. “But I’ve painted for 25 years, I’ve met a lot of my goals in that domain, and now the village is my canvas. It’s a place to exercise my creativity, my work ethic. I think there are some direct skills from being an easel painter that apply here: essentially, imagining what doesn’t exist yet; being able to envision it. It’s like looking at a blank canvas. You can see where you want to go, then you just figure out how to get there.”