A History of New York City’s Water System

Upstater Magazine Spring 2016 | By Leander Schaerlaeckens

New York City’s water has come a long way. It flows 145 miles from its furthest reservoir—Cannonsville, near the Northeastern corner of Pennsylvania—to Staten Island. It’s also expanded from a few wells—at times carrying yellow fever, cholera, and typhoid—to one of the world’s vastest and cleanest water supply systems.

The city’s water system was long racing to keep up with the demands of its mushrooming population. The first water shortage was reported in 1774, when the city had just 22,000 inhabitants. The first public well opened near Bowling Green in 1677, with more wells following on street corners. A reservoir was later made at Broadway and White Street and water pumped through hollow logs to distribute it, but with no sewer system, the water was notoriously fetid. A 1789 outbreak of yellow fever, one of several scourges attributed to the foul water supply, killed 2,000 New Yorkers, about six percent of the population. Five more major yellow fever epidemics and four cholera outbreaks followed. Ships traveling to New York carried enough water for the trip back as well, rather than fill up in the city.

Regardless of the water’s quality, there wasn’t enough of it. By 1830, with reservoirs built out further and 40 miles of wooden pipes laid, the infrastructure still only served 60,000 of the then 200,000 Manhattanites.

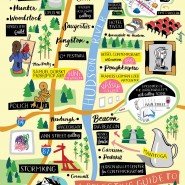

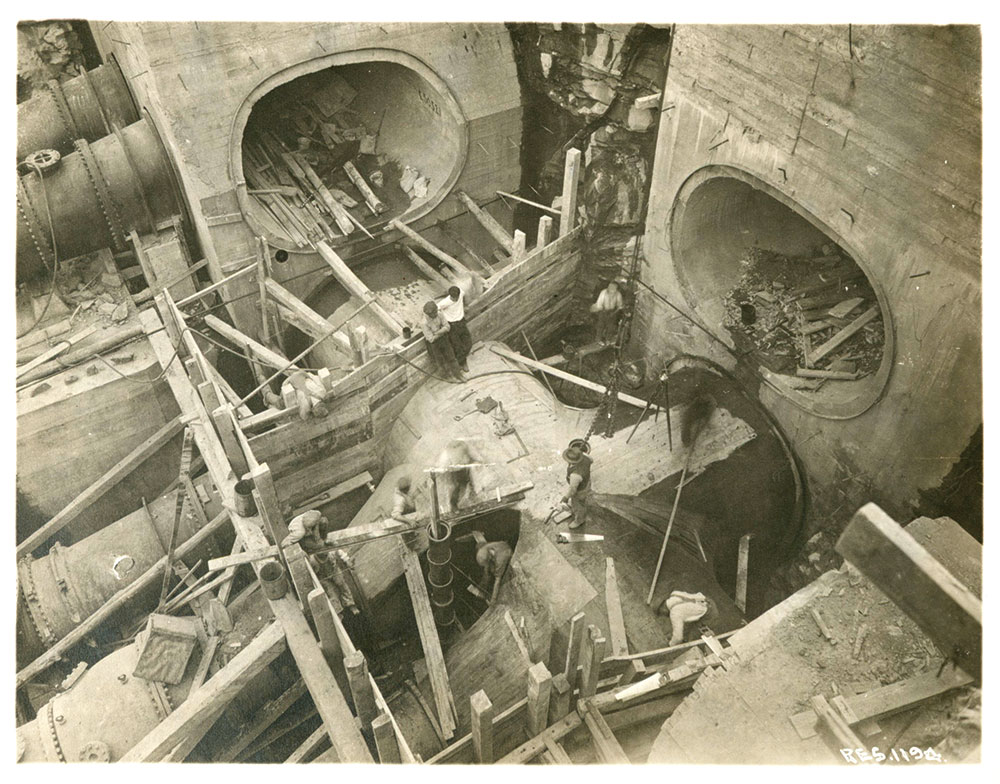

In 1842, a dam was built on the Croton River and an aqueduct laid into Manhattan, now known as the Old Croton Aqueduct, marking the birth of New York City’s modern water system. Water quality improved, and service hasn’t been interrupted for anything other than maintenance since the Croton Aqueduct opened, but shortages continued until 1890, when a second aqueduct was built from the Croton watershed. Shortages abated but new sources needed to be tapped to stay ahead of population growth. The Catskill aqueduct was opened in 1915, followed by the Delaware aqueduct in 1944, which was eventually extended with the reservoirs that still feed into it today.

The city’s expansion of its water system was often controversial. Following political maneuvering in the early 19th century, Columbia and Dutchess counties were bypassed, and the city’s water was sourced entirely from the Hudson River’s western bank. Planners tried to avoid building tunnels underneath the river, but eventually ran out of options and the Catskills had to be tapped. The Catskills line was built in 1915, crossing the river between Storm King and the West Point Military Academy, dipping 1,100 feet below sea level to pass underneath the base of Bear Mountain.

The upstate communities whose natural resources would quench the city’s endless thirst never got much of a say in the matter. In Albany, New York City was seen as the engine of the state’s economic progress and accommodated without question. The city freely gobbled up whatever water resources it demanded. Farms and other properties were seized and owners weren’t always compensated fairly.

Critics say the city didn’t get serious about water conservation until the 1980s, instead, expanding its system rather than building efficiencies into it. Nor was the Hudson River ever seriously considered as an alternative. Rather than make an effort to clean it up and filter its water, the city simply argued that it was too dirty and that it needed the already clean water upstate.

Today, the system has a reservoir capacity of 552.5 billion gallons of water, which is typically 85 percent filled. The largest of those reservoirs is the Pepacton, at 140.2 billion gallons. Along the way to the city, the water is disinfected with ultraviolet light, tested for purity at 1,000 different stations, and treated with chlorine; for every million parts of water, one part of fluoride is added. A security force of about 200 officers, once called the Aqueduct Police and now known as the DEP Police, protects the water supply.